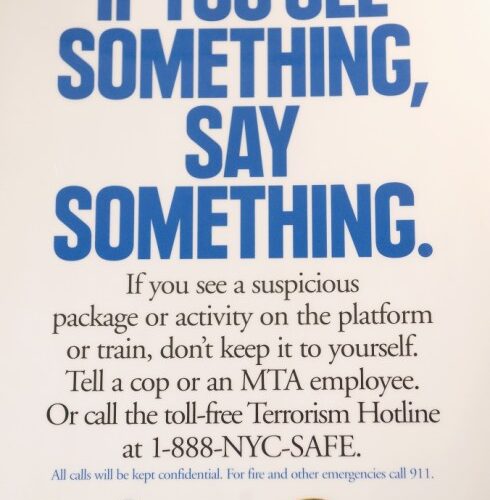

How many times have we seen and heard the admonition “if you see something, say something.” Well, I recently saw something and said something, but nothing was done. Here is the story. I went to the Metropolitan Opera last Saturday night to see one of my favorite operas, “Don Giovanni.” When I got to my seat, I saw a very large backpack in the seat next to me. Nobody was in the seat. Only the backpack was there. I waited a few minutes but no one showed up.

Imagine if this happened at an airport: unattended luggage would immediately raise suspicion. Experience has shown that electronic plus human perception constitute the best protection. That is why we are told to say something if our eyes see something suspicious. The assumption is that the vast majority of suspicious items will turn out to be harmless but why take chances with our safety.

So I said something. I politely asked an usher to alert security. For 15 minutes, no one showed up. The seat remained empty as the time for the performance grew closer and I got more nervous about the unattended backpack. Sure, the owner probably left it on the seat and went to the bathroom or for a drink. But as more time passed, I worried about the unlikely possibility that a terrorist might have placed the luggage and then left. Probably not, but that has happened in the past.

A few minutes later, the Met sent a young man who apparently looked at the item from a distance and said nothing. He didn’t even identify himself. There was still no one in the seat.

The usher then asked me if I was satisfied that there was no problem because a security person had observed the knapsack. I told her that no one even spoke to me though I was sitting right next to the item. She told me she would contact a security supervisor.

Finally a senior security person arrived and told me that the policy of the Met was to allow any packages to remain on seats even in the absence of anyone in the seat. He told me the backpack, like all items, had been subject to a routine check when the seat holder entered the hall.

I responded that this was not sufficient: all airport packages and luggage are also checked, much more thoroughly than the perfunctory peeking and wanding at the Met. But even at an airport, if luggage that has gone through security is seen without a person accompanying it, suspicion is raised. That’s when we are supposed to say something. Just to be absolutely sure.

The security maven reiterated that Met policy as allowing unattended packages to remain on seats, even if the program begins! I told him that if the seat holder didn’t show up by curtain time, I would leave. But that wouldn’t eliminate the potential dangers to others.

The security official then asked me for my name, which he duly noted down with an aggravated look.

Fortunately the seat holder finally arrived a few minutes before the opera began. His presence assured me that we were safe.

My wife thinks I overreacted and she is probably right. The likelihood of danger was extremely low. But we have been repeatedly advised by government agencies to say something even when we see something that is suspicious but almost certainly innocent.

Better safe than sorry is a cliché, but it represents a priority that prefers many false positives (inspecting parcels that turn out to contain nothing dangerous) over the chance of even one false negative (failing to search a package that turns out to contain explosives).

I have just published a book called “The Preventive State: The Challenge of Preventing Serious Harms While Preserving Essential Liberties.” Its thesis is that preventive actions, such as inspection of suspicious packages must be balanced against intrusive violations of privacy.

This is never an easy balance to strike, but every society must decide whether to strike it in favor of safety or privacy. My experience at the Met was a small example of this challenge. I decided to strike the balance in favor of alerting security to a possible if unlikely danger. The Met decided to strike it in favor of doing nothing. It turned out that there was no danger— in this case.

But I will continue to say something whenever I see something suspicious, even though I now have a “record” at the Met of being an overcautious pain!

Dershowitz is a professor emeritus at Harvard Law School and author of many books.