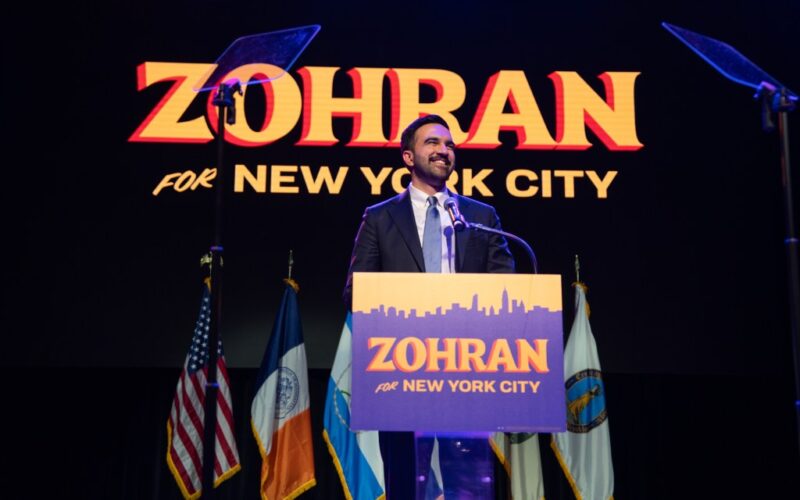

Zohran Mamdani’s insurgent win has spawned endless political analysis. But so far, the punditry has missed a crucial factor that made his unlikely bid for mayor possible in the first place: New York City’s longstanding, public matching funds program, one of the last gasps in a post Citizens United world against the influence of big money in politics. The program has been widely recognized as a model for the country.

Nearly 40 years after the program’s inception, mayoral candidates can now receive $8 for every $1 donated by individual New Yorkers, up to $250 per donor. The matching ratio allowed Mamdani to hit the spending limit in both the primary and general elections — freeing the candidate to campaign for votes instead of dollars. In what other system would a candidate be able to tell supporters not to donate any more money to his campaign?

Former Gov. Andrew Cuomo, Republican Curtis Sliwa, and outgoing Mayor Adams also chose to participate in the matching funds program. Their participation provided an incentive for their campaigns to seek out small dollar donors, thus pushing all four campaigns to make their case to a broader audience, not just to moneyed interests. The major contenders, Mamdani and Cuomo, had 52,560 small donations and 7,772 respectively.

In the end, the candidates raised $6.7 million (Adams), $6 million (Cuomo), $4 million (Mamdani), and $1.5 million (Sliwa) in private donations. In turn, they received about $13.1 million (Mamdani), $8 million (Cuomo), $5.3 million (Sliwa), and none (Adams) in public matching funds. The discrepancy between private donations and public funds comes down to different types of donations: donations under $250 from New York City residents are eligible for public match, whereas larger donations and out-of-towners are not.

The final fundraising figures also tell a story about accountability and transparency. While Adams raised plenty of private donations, the Campaign Finance Board repeatedly found his campaign was not eligible for matching funds on the grounds of 1) failure to submit adequate documentation and 2) reason to believe the campaign broke the law. No candidate is entitled to public funds; they must all follow the rules. In the end, Adams dropped out of the mayoral race after the deadline to be removed from the ballot.

For candidates who do heed the program’s rules, it can be transformational. Matching funds yielded the resources Mamdani needed to attain his high visibility and win the primary and then similarly set him up to become known widely enough to propel him to win the general election. Even with a generationally popular candidate, both these successes were by no means predictable.

While matching funds provide an important counterbalance to big money, “independent” spending remains a factor. Both Mamdani and Cuomo benefitted from super PAC spending, but that spending strongly favored Cuomo by millions of dollars.

Still, despite an influx of spending in support of Cuomo from billionaire backers like former Mayor Mike Bloomberg and hedge fund manager Bill Ackman, as well as businesses like DoorDash and Airbnb, Mamdani was able to raise enough money — almost seven times more — from small donors and millions more in public funding — to spend competitively on his campaign through matching funds.

It is very possible, even likely, that Mamdani and his grassroots movement would have lost against so much big money, were it not for the public funds he received.

The result in this election was that, while moneyed interests were in play, New Yorkers with fewer dollars to spare still had a reason to participate in the lead-up to Election Day, armed with the knowledge that their small donations could have a big impact. Past city elections demonstrate that New York’s program has increased the breadth both of donors and of candidates, by making it easier for candidates who are not connected to wealthy donors to run for office and by increasing civic participation.

Cuomo, aided by outsized super PAC spending and by far greater name recognition, could not overcome the power of thousands of small donors whose contributions yielded millions of dollars in public matching funds. This election, in which Mamdani received more than five times as many small contributions as did Cuomo, reflects these phenomena.

There are many factors that go into a winning campaign; individual candidate quality, policy positions, and messaging, to name a few. But money is a powerful tool that can squash insurgent candidates quickly. The matching funds system not only gives them a fighting chance — it even makes it possible for them to win.

Gordon was the founding executive director of the New York City Campaign Finance Board from 1988 to 2006.