Everyone can agree there is an affordability crisis plaguing the New York City housing market. When folks cannot afford quality housing, thriving here becomes untenable, and the rich diversity of talent that makes our city the best in the world is lost. Amid an economic recovery, government officials and the real estate industry have a shared responsibility to address this crisis head-on.

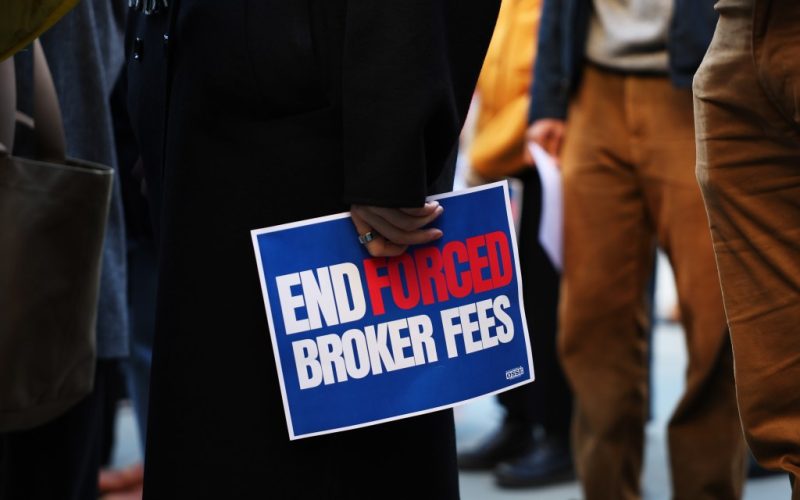

Unfortunately, the recently passed Fairness in Apartment Rental Expenses (FARE) Act does precisely the opposite. Instead of offering real solutions, the City Council voted to force New York tenants to beta test their experiment to see what happens when transparency, choice, and professional accountability are removed from the rental marketplace.

Deceptively marketed as a vehicle to end tenant-paid brokerage fees, FARE would more accurately be called the “Bait & Switch Act,” as it will lead to renters paying much more in commissions, more often — while enjoying less transparency of information.

This is primarily because regardless of whether property owners engage an outside broker or hire in-house salaried staff to manage their vacancies, produce accurate online listings, create marketing content for the public, answer prospective renters’ questions, manage in-person showings, and streamline the application, approval, and move-in process for new tenants, costs for these necessary services are offset by owners’ one source of revenue — rent.

Accordingly, landlords have already publicly laid out specific plans to spread their anticipated additional costs into the rent of every free market unit over the next 24 months, if FARE should be implemented. Overwhelming data already exists demonstrating that so-called “No Fee” listings in New York are 10% to 30% more expensive than those which are not. And those higher rents compound over the life of the tenancy, as opposed to being a one-time negotiated cost between a tenant and a service provider.

Even more troubling, many landlords of highly coveted rent-stabilized units will choose not to officially hire any brokers if FARE takes effect. Instead, they’ll simply provide their vacancy list to a small group of agents to share at-will with prospective tenants, who then must hire them for exorbitant tenant-paid fees to learn anything at all about those apartments.

The result? The industry may well devolve back to a chaotic time when word of mouth “whisper listings,” inaccurate addresses, misleading pricing, and generic photos would be the main avenue for renters to find rent regulated housing, with a small handful of unaccountable gatekeepers maintaining control over a shadow inventory.

Moreover, if owners cannot easily find quality tenants through those methods, some low-cost rent stabilized apartments may also be taken off the market entirely, like we have already seen happen with tens of thousands of units since the state’s Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act of 2019 was passed and many property owners determined that they couldn’t afford to keep their aging inventory up to code.

This bill could spur the single largest rent increase for tenants in recent memory — while simultaneously reducing transparency, access, and consumer choice in the process.

FARE proponents have said that market forces determine rent prices, and if landlords could raise rent to pay for broker fees, they would have already. A simple understanding of the history of New York’s housing policy as well as the concept of supply and demand refutes that premise.

Last year, the city received building applications for fewer than 10,000 new multifamily units, compared to the 20,000 produced annually between 2000 and 2020 and the 500,000 new units needed by 2030 to keep pace with projected population growth.

There is a significant housing supply deficit that will continue to put upward pressure on rents, and which FARE fails to address. In fact, when similar legislation to FARE was briefly in place in 2020, citywide rent on affected properties spiked by at least 6.1% on average in only one week.

There’s so much substantive work to be undertaken to meaningfully improve the lives of New York City’s renters, including creating more affordable housing, protecting more rent-regulated inventory, and fixing our broken public assistance voucher system. I believe many of the FARE Act’s supporters have good intentions to reduce housing costs and create a better home search process.

However, the Council’s bill is an affront to renters who are desperately seeking solutions to the affordability crisis, and the politicians who voted for it should be held accountable the next time we see our monthly rent bill increase — again.

Hourigan is senior managing director and director of professional development at Bond New York Properties. He also serves as the co-chair of the Real Estate Board of New York Residential Rental Committee.