The roots of Irish and African solidarity can be traced to colonial times, when enslaved Africans and indentured Irish servants interacted on British-owned estates in North America.

While historical tensions have been acknowledged, a shared activism highlighted this relationship between Blacks and the Irish in the United States. It would be defined by social, cultural and political synergies, with interesting outcomes.

Today, approximately 38% of Blacks in the U.S. have some Irish ancestry, estimates the African American Irish Diaspora Network (AAIDN) organization, which “fosters relationships between African Americans and Ireland through shared heritage and culture.”

The Network notes celebrities such as entertainers Beyoncé and Alicia Keys, former NBA star Shaquille O’Neal and President Barack Obama have Irish genes, as did boxing great Muhammad Ali and Gen. Colin Powell.

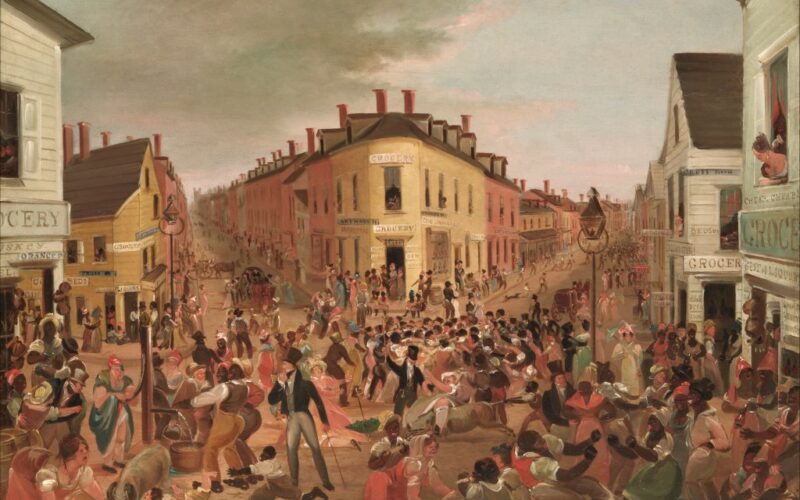

The bonding between enslaved Africans and Irish servants, which began in the 18th century, would continue in the 19th century. From the 1830s to the 1860s, the Five Points neighborhood in New York — historically depicted as a violent, disease-ridden and poverty-stricken place — was home to many Irish, Germans and African Americans. It also served as a safe haven for escaped slaves in a state where slavery was abolished in 1827.

“Originally the site of New York City’s first free Black settlement, by 1850 the Five Points district in lower Manhattan had instead become infamous for its dance halls, bars, gambling houses, prostitution, and for its mixed-race clientele,” noted the online African American reference center Blackpast, founded by former University of Washington professor Quintard Taylor.

In the dance halls, Black and Irish musicians and dancers competed, helping complete the fusion of Irish jigs and African gioube (sacred and secular stepping dances) that went back to the 18th century and eventually evolved into tap dancing — a uniquely American dance form.

Early styles of tapping called for hard-soled shoes, clogs or hobnail boots. It was not until the early 20th century that small metal plates (or taps) appeared on shoes of dancers on the Broadway musical stages, making tap dancing a phenomenally popular form of entertainment.

Further north in Manhattan, in the mid-19th century, was Seneca Village, another community of Black and Irish residents. Located on what is now the perimeter of Central Park from W. 82nd to W. 89th Sts., Seneca Village had approximately 225 residents by 1855. According to the Central Park Conservancy, two-thirds of the residents were African American; many were property owners, one-third were Irish immigrants and the remainder were newcomers of German descent.

Because Irish and African American communities often found themselves in similar lower-working-class positions, alliances inevitably formed.

On the political front, one of the earliest and most significant examples of African American and Irish collaboration was legendary abolitionist Frederick Douglass’ transformational four-month trip to Ireland in 1845. Ireland was fertile ground for Douglass’ passionate abolitionist message.

He spoke out in support of Irish independence, highlighting the similarities between the Irish struggle and the fight against slavery in the U.S. He also used the trip to promote his recently published autobiography, “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave.”

“I can truly say, I have spent some of the happiest moments of my life since landing in this country. I seem to have undergone a transformation. I live a new life,” Douglass wrote to fellow abolitionist and journalist William Lloyd Garrison on Jan. 1, 1846, the day he left Ireland.

Douglass met a strong ally in Daniel O’Connell, who was hailed as “The Liberator” in Ireland. In 1845, O’Connell said, “I despise any government which, while it boasts of liberty, is guilty of slavery, the greatest crime that can be committed by humanity against humanity.”

Born in Macon, Georgia in 1834, Patrick Francis Healy was son of an Irish immigrant and a slave, who were later joined an interracial common-law marriage. Passing as a white man, Healy became the first Black to attain a PhD and the first Black to head a predominantly white university. He became president of Georgetown University in 1872. He was also the first to Black to become a member of the Catholic’s join the Jesuit order.

Generations later, the fight for equality would be aided during President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal era by his Irish-American attorney general, Frank Murphy, who established the Civil Rights Unit of the Department of Justice. Murphy actively supported the NAACP and fought against discrimination.

Ahead of Martin Luther King Day in January 2013, an Irish Examiner story about Dr. King mulled that he had Irish ancestry from his paternal great-grandfather, Nathan King. According to one census report, Nathan King was born in Ireland.

In a 1985 speech at the University of Massachusetts, John Hume, Irish nationalist politician and future Nobel Peace Prize winner, declared: “The American Civil Rights movement gave birth to ours. The songs of your movement were ours also.” The Chicago Tribune hailed Hume as the “Irish Martin Luther King.”

Despite the Black-Irish solidarity, there were a few lows in the relationship at first; sometimes these were due to competition for jobs and housing, or discriminatory attitudes towards Blacks by some Irish immigrants.

In Manhattan, during the Draft Riots of July 1863, thousands of poor and desperate immigrants — many of them Irish — went on a three-day rampage. The violence perpetrated by working-class white men was in response to America’s first Army draft, which forced men to join the Union Army during the Civil War.

First, the rioters set fire to the draft office. Then, they targeted Blacks, their establishments and institutions. At least 119 people died in the riots, including 18 Blacks,16 soldiers and 85 rioters.

“So there’s always been a relationship between Irish folks and Black folks, historically,” said Keith Wright, the former New York State Assembly member who now sits on the African American Irish Diaspora Network’s board of directors.

“And quite frankly, not enough has been told about the story between the struggles of Black folks and Irish folks, and their struggles together. And I think that the AAIDN will highlight that and try and reconnect the two cultures together — because historically, they’ve been together.”