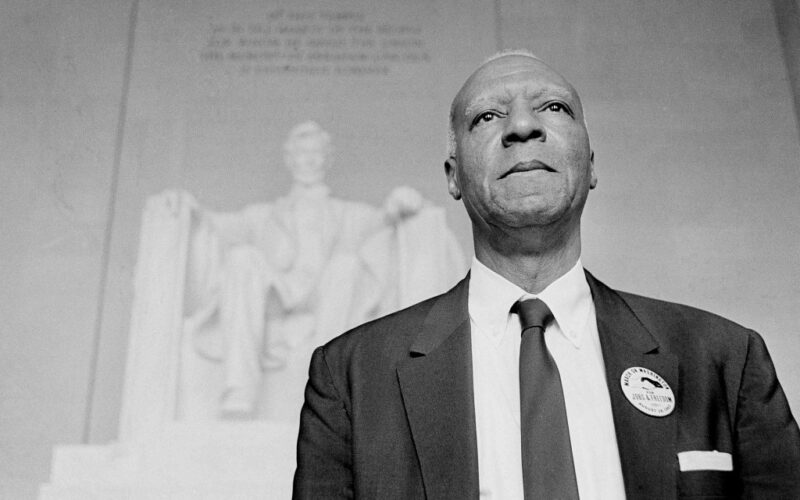

Rightfully, a host of tributes across America recognize the achievements of pioneering Black union leader A. Philip Randolph — his historic founding of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters union, and pressing U.S. presidents to act against federal discrimination before the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

In 1989, a U.S. postage stamp marked the 100th anniversary of his birth; schools and streets bear his name, and then there’s the Pullman National Historical Park — a National Parks Service historic site. The nonprofit National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum is also located in Chicago, which was home to the once-powerful Pullman Company that manufactured railroad cars and created innovative railroad sleeper cars.

Here in New York City, public schools are named for Randolph, and the Borough of Manhattan Community College’s main library memorializes him. But the most visible and fitting tributes to the legacy of Randoph are the Black labor leaders and union executives who now hold office and work to improve working conditions and benefits for their organizations’ members.

The city’s Black labor hierarchy includes George Gresham, president of 1199SEIU; Constance Bradley, president of Transport Workers Union Local 101; Greg Floyd, president of Teamsters Local 237; Wayne Spence, president of New York State Public Employees Federation; Gloria Middleton, president of CWA Local 1180; Shaun Francois, president of Board of Education Employees Local 372; Nneka Ogwumike, president of Women’s National Basketball Players Association; Dalvanie Powell, president of United Probation Officers Association (UPOA) and Nancy Hagans, president of New York State Nurses Association (NYSNA).

“Today’s labor leaders and activists stand on the shoulders of giants like A. Philip Randolph, who understood that workers’ rights and civil rights are essentially linked,” said Hagans, a registered nurse at Brooklyn’s Maimonides Medical Center. She leads NYSNA — “New York’s largest union and professional association for registered nurses, representing more than 42,000 registered nurses and healthcare professionals across the state,” according to the union.

Hagans navigated her frontline workers through the COVID pandemic and won substantial victories for her union’s members in “safe staffing legislation, wages and benefits, health [and] safety — victories for the city’s private sector nurses,” and pay parity in 2023 for public sector nurses, according to NYSA.

Hagans began her union activity when she was denied a day shift in the hospital’s intensive care unit; nurses of color were relegated to the night shift. When she challenged the hospital’s unfair policy and won, a union representative asked Hagans to get involved and help other union members who had grievances. After holding several high-ranking positions in NYSNA, Hagans was elected president in 2021.

According to NYSNA, Hagans was “instrumental in NYSNA’s affiliation with National Nurses United (NNU), AFL-CIO, in Oct. 2022, bringing NYSNA into the larger national labor movement” and persevering for union members.

“We continue in his spirit to fight for racial justice and the dignity of all workers,” Hagans said.

Powell, UPOA president since 2016, is the first Black woman to hold the post in the union. Its members are predominantly women of color. The union represents probation officers, supervisors officers and more than 500 retirees. Active in the union since becoming a delegate in 2016, Powell says she has held “every position in the union except treasurer.”

“We’re the alternative to incarceration,” Powell said of the probation workers, adding, “I absolutely believe in second chances.” Since taking the helm at UPOA, Powell has negotiated a new contract with the city with no cuts or givebacks, secured additional health and wellness benefits for active and retired members, and is waging an ongoing battle to end pay disparities that affect her union’s members. Hiring and staffing policies are also among the organization’s concerns.

Pay disparities are some of the UPOA’s main grievances, and Powell says she strongly relates to Randolph’s efforts to improve pay and working conditions for the Pullman porters.

“I would love to be a female version of Mr. Randolph,” Powell admits. “I would love to be that person! I’m following in his footsteps. His legacy lives on in people like me and others. We as people, people of color, have to realize that we haven’t arrived. I think a lot of people think that we have arrived, and we still have a long way to go.”

Powell plans to share Randolph’s legacy and a piece of his wisdom with the UPOA this month.

“I was looking at a quote that Mr. Randolph made,” she said. “I thought it was excellent. Matter of fact, I’m going to use it in my next newsletter” for Black History Month.

“It says, ‘Freedom is never granted: It is won. Justice is never given: It is exacted. Freedom and justice must be struggled for by the oppressed of all lands and races.’ ”

Randolph initially gained fame for his work in the American labor movement, and he used his clout to win bold victories in equality before the Civil Rights Movement began in the 1950s and 1960s.

Randolph — who moved to New York City in 1917 after excelling in school in his birthplace of Crescent City, Florida — earned recognition by founding the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) union in 1925. The organization was the first predominately Black labor union in the U.S.

The Illinois-based Pullman Company, started by George Pullman in 1867, “was the largest employer of African Americans, purposefully hiring formerly enslaved people to achieve the high-quality customer service,” according to the Library of Congress’ 2023 “This Monthly Business article,” “Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters Union Formed.”

The company’s Pullman sleeper — designed by Pullman and Ben Field in 1865 — was designed and introduced to provide comfortable nighttime travel. The primarily Black staff of porters were the vital component of the Pullman Company’s exclusive sleeper car service.

The Pullman sleeper car was a railway passenger car that also provided accommodations for comfortable daytime travel. Its accommodations included fold-down berths for sleeping, a toilet, light provided by candles, and heat from a coal or wood-burning stove.

Pullman sleeping cars’ high-quality customer service required porters to tote luggage, serve food, shine shoes, wake passengers, clean berths, make beds, comfort crying babies and perform myriad other duties to ensure a comfortable trip for passengers. Black workers, barred from becoming conductors or holding better-paying railroad jobs and relegated to the porter positions, “endured poor working conditions; working long hours for little pay,” according to the Library of Congress’ article.

Though Black workers were supposed to receive tips to boost their meager earnings, they had to pay for their meals and uniforms and also had other job expenses. In addition to the compensation insult, they were often the targets of racial abuse from passengers.

Randolph, known as a strong workers’ rights advocate, was favored to help form the union because he was not a Pullman Company employee, and could not be fired for unionizing.

The BSCP’s union organizing drew pushback from the Pullman Company, the American Federation of Labor and even Black American leaders who were satisfied that the railroad company’s efforts made Pullman porter jobs one of the higher-paying positions available to Black Americans, and aided the growth of the Black middle class in the U.S.

“It took twelve years from the formation of the union for a contract with the Pullman Company to be signed and for the AFL to recognize the BSCP as an international charter,” according to the Library of Congress.

The BSCP joined the American Federation of Labor (AFL) union in 1937. However, Randolph removed BSCP from the AFL in 1938 to protest continued racial discriminatory practices, bringing the Black union into the newly formed Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Randolph served as union president and used his new-found national notoriety and clout to make gains for Black Americans.

When President Franklin Roosevelt refused to issue an executive order banning discrimination against Black workers in the U.S. defense industry in 1941, Randolph called for up to 100,000 “loyal Negro American citizens” converge on Washington, D.C., for a nonviolent protest march. Less than a week before this planned march on Washington, President Roosevelt issued an order stating “there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin.”

In 1948, Randolph got President Harry Truman to end military discrimination “as quickly as possible” by threatening “widespread civil disobedience” and the loss of Black votes for the president’s reelection bid.

In 1955, when the AFL-CIO was formed in a merger, Randolph served as elected vice president of the joint labor organization.

Randolph was a key organizer of the historic 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the estimated 250,000-person nonviolent protest by members of labor unions, civil rights organizations and religious groups.

He retired as president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in 1968 and left his AFL-CIO post in 1974. The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters merged into a larger union in 1978, and exists today as the Transportation Communications Union/IAM, mainly representing railroad industry workers.

After a lifetime of achievement, Randolph died in 1979, leaving a living legacy of Black labor leaders to follow him.