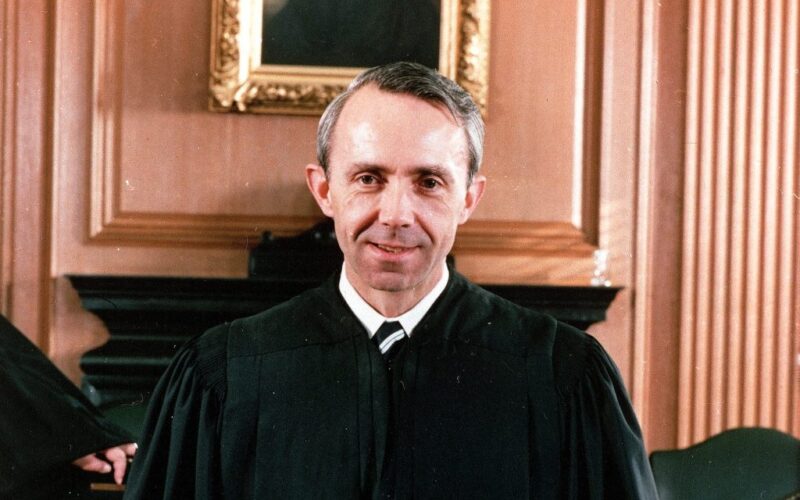

David Souter, longtime justice on the U.S. Supreme Court and by all accounts a very good man, has passed away. A ruling he signed onto allowing broad use of eminent domain by the government, even to allow the transfer of property from one private owner to another, lives on. It is high time to reexamine the use and abuse of the authority, especially here in New York.

The case was Kelo vs. City of New London, in 2005. Five votes (including Souter’s) to four, the high court blessed the seizure of Connecticut homes to hand the land to a private developer as part of an economic redevelopment plan.

Susette Kelo and her fellow homeowners said that violated the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause (“nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation”) — but the court disagreed, defining “public use” so broadly as to render it meaningless.

And so, a sweeping government power that had once been reserved for the construction of parts of common public infrastructure like schools, reservoirs, highways and parks was formally extended to almost anything the government determined to be a priority.

New York’s expansive use of eminent domain needed and still needs reining in, not expansion. In the mid-20th century, widespread condemnation of neighborhoods as “blighted” paved the pockets of private interests to advance theoretical, and often only theoretical public benefits.

We backed the Atlantic Yards redevelopment project in Brooklyn, but it should have given anyone concerned about property rights pause to see 22 acres seized for a profit-making arena and condominiums. Technically, everyone whose property is seized gets fair-market compensation — but it’s hard to compensate for a home uprooted or destroyed.

In Atlantic City a half century ago, casinos surrounded a house owned by a retired widow named Vera Coking — and high rollers desperately wanted her out. In the late 1970s, Penthouse publisher Bob Guccione offered her $1 million; she said no.

In the 1990s, a magnate named Donald Trump tried to buy her out — then persuaded Jersey’s Casino Reinvestment Development Authority to exercise its eminent domain power to take Coking’s property. Coking lost her house and got a quarter of a million dollars.

She challenged the seizure and won, drawing a clear line that stayed in place in many if not most American states, at least until Kelo erased it.

Here in New York, even when the end goal is a traditional public works project, like the proposed redevelopment of Penn Station, the ease with which the state can order large swaths of land “blighted” and therefore clear them away is disturbing. The area around Madison Square Garden is not blight by any honest definition of the term.

Eminent domain is an important tool for truly essential and truly public purposes. Indeed, the government can and sometimes should seize intellectual property such as during a public health emergency, the feds might very well seek to acquire a new drug from a pharmaceutical company.

But none of this should be easy. The United States is a place where property rights should by default be respected and protected.