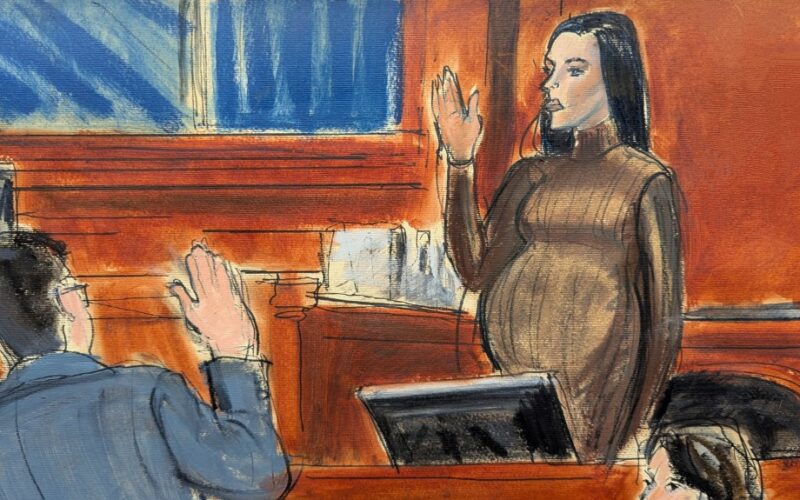

This week, Cassie Ventura testified in a Manhattan federal court in the sex trafficking and racketeering criminal case against her ex-boyfriend Sean “Diddy” Combs and relived the horrifying memories of her years-long abuse. She spoke about Combs hitting her across the face, kicking her, and living in fear that the media mogul had her “career in his hands.”

Her allegations, in all their tragic and stomach-turning details, are far from uncommon. In fact, as a lawyer specializing in human trafficking, I’ve heard versions of this same story more times than I can count.

Too often, we reduce the problem of sex trafficking to its most clear-cut examples. We think of teenage girls disappearing from their homes and showing up in brothels and roadside motels on the other side of the world. We think of international sex trafficking rings, and we convince ourselves that sex trafficking isn’t a problem here in the United States.

As Ventura’s testimony brings to light, sex traffickers are oftentimes more covert than we give them credit for — they opt for the weapons of power and influence rather than the shackles we see in movies. They lure their victim in with promises of love and success, and they trap them with threats to their careers and reputations. This is how scores of sex trafficking cases unfold, and they’re happening in the most common places every day.

For decades, Combs masked himself as a wealthy music mogul who liked to throw lavish parties and surround himself with women. It took decades to uncover the dark underbelly of his reputation: the case against him states he was a predator who repeatedly used violence and intimidation to force sex on women. If the allegations against him are true, he’s the definition of a human trafficker, and for most of his life, no one did anything to stop him.

You don’t need to look far to find other human traffickers getting away with Combs’ same tactics. Take, for instance, the civil lawsuit unfolding against former World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) Founder and CEO Vince McMahon in Connecticut federal court. Like Combs, McMahon is accused of raping his former employee Janel Grant and forcing her into sexual acts with everyone from Brock Lesnar — a wrestler WWE sought to hire — to production staff and construction workers Grant had never met.

Just as Combs silenced Ventura by controlling her career, according to Grant’s complaint, McMahon got away with his heinous behavior by insinuating he could either make or break her reputation in the entertainment industry. WWE is one of the biggest employers in Connecticut — McMahon also has resources and political influence that he uses to his advantage.

Under U.S. federal law — specifically the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) — human trafficking includes the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or commercial sex through the use of force, fraud, or coercion, or where the victim is a minor.

As a law professor and expert in this field, anyone who uses coercion, abuses their power, and exploits their victims’ vulnerabilities is a human trafficker. It might not look like what we saw in the 2012 film “Taken,” but this is the reality of many human trafficking cases around the world. The fear of losing your career, your livelihood, and your future in an industry can shackle women to their abusers for years in the same way physical restraints do. It happens far too often, and those with the power to stop it are standing by.

That needs to change. We need to learn what sexual assault and human trafficking look like, we need to stay vigilant for their signs, and we need to commit to speaking up. As the allegations against Combs and McMahon show, human trafficking is happening in plain sight — and until institutions and everyday people commit to stopping it — we are all complicit.

Carr is clinical professor of law and director of the Human Trafficking Clinic at the University of Michigan Law School. She is also a faculty affiliate at the Center for Positive Organizations at U-M’s Ross School of Business. The opinion expressed above is hers and not of the law school.