They say reporters are not supposed to insert themselves into a story.

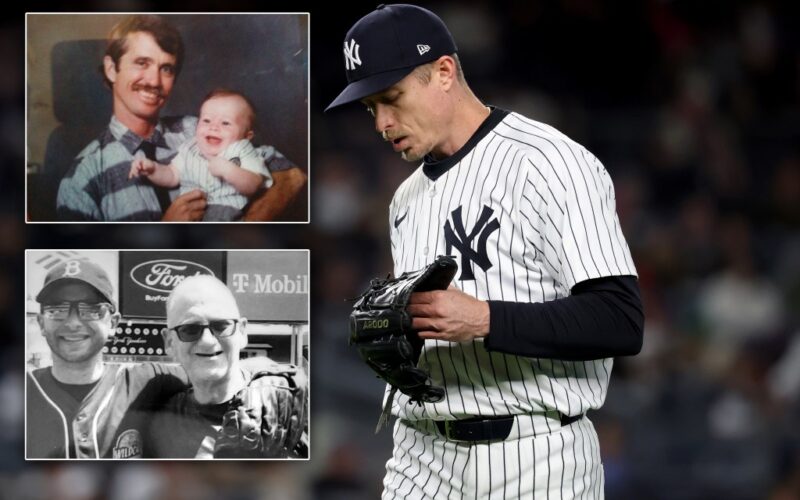

But the truth is, I would not have spent 40 minutes talking to Yankees pitcher Tim Hill if not for our shared grief. I would not have taken up so much of his time had I not thought — or hoped — that he had insight on how to navigate a path he’s already charted. I would not have asked a side-arming reliever about genetics had we both been able to ignore what’s in our DNA.

And I certainly would not have peppered him with questions about the premature death of his father had my own dad’s passing on Jan. 16 not been weighing on me ever since.

“I’m sorry to hear about your dad. That’s f–king fresh, bro,” Tim said with Father’s Day approaching. “I can’t imagine — because it happened to me, but it was so long ago.

“I’m in such a different place now.”

* * *

About two years after being diagnosed with colon cancer, Jerry Hill died on Sept. 13, 2007 at age 53. Keith Phillips died of prostate cancer earlier this year, less than a month before his 63rd birthday and six years after his initial diagnosis.

Tim was 17 when his dad died. I was 30 when mine passed.

“It’s never f–king easy, dude, no matter what,” Tim said. “Even if they die at 100 years old and they had an amazing life, you’re still gonna be f–king sad about it. It sucks no matter what. And a lot of times, it’s more devastating when you still need them.

“I’m sure you feel like, ‘I still f–king need him.’”

He’s right, and in the moments that I realize this and think to call my dad, it pains me that I can’t. I mostly have good days at this point, but I still tear up. I still get angry. I still feel guilt. I still think it’s not fair, even as I scold myself for sounding like a child.

Grief is a massive wave of thoughts and emotions, ambiguous and unrelenting. Triggers lurk around every corner. It is unpredictable and inevitable all at once.

“It could be anything, bro,” Tim says of the daily norms that upset him.

I can relate, but I am fortunate that my dad lived to see me become an adult, and that we were able heal some old wounds. I’m grateful that some of our best memories came after his diagnosis, even if I feel robbed of time.

Now 35, Tim was only 15 when he found out his dad had Stage 4 cancer, the most advanced stage.

Still developing as a person, he said he was “lost” for a while after that, his lack of direction only worsening once Jerry died. A self-described “punk-ass kid,” Tim took advantage of his parents’ preoccupied attention, acted out, and was kicked out of “several” high schools.

He dropped out his junior year.

“I was a s–thead,” Tim said, disappointment in his voice. “I was going through it. I was getting in trouble at school. I think about it now, and I’m like, ‘F–k, the last thing that they probably needed at that time was me acting like an asshole.

“I regret that. That sucks.”

All these years later, Tim still feels some of the things I’m learning how to process, if only from time to time. That’s not to say we’re miserable — we’re not — but all the parts that make up grief still bubble beneath the surface. Maybe they always will, I think, as I transcribe our conversation.

As Tim spoke, it occurred to him that his dad has been gone longer than he was in his life.

The thought hurts.

“It’s sad, s–t like that,” Tim said. “Sometimes I think about things and I try to remember what his voice sounded like or stuff like that, and it’s tough when it’s been so long.”

While Tim tries to remember, I mourn secondary losses, the milestones I’ll never get to share with my dad. He won’t be there when I get married. He won’t get to be a grandpa. He won’t see where my career, which he was so proud of, takes me.

The thoughts hurt.

Leaning on loved ones helps. For me, it’s been my girlfriend, sister and mom. Tim eventually straightened himself out with the help of his mother, Teri, and older sisters, Kristi and Amy.

Counseling also makes a difference.

Tim did not seek professional assistance when his dad died, but he has talked to someone in recent years for various reasons. Those conversations often circled back to Jerry.

I started seeing a grief counselor shortly after my dad died. I continue to schedule sessions. If nothing else, it gives me an excuse to talk about my dad and process my grief as other parts of my life keep me busy and distracted.

“I think it’s good,” Tim said. “Even sometimes you’ll feel sh–ty afterwards, but it’s good to talk about it and the things that still bother you.”

However, the most important thing, Tim said for anyone going through something similar, “would be to try and find something that serves you.”

Baseball has been that something for both of us in a way.

* * *

Now in his eighth MLB season, Tim “started giving a s–t” — in school and on the field — around the time he turned 21. He began his college career at Palomar, a JUCO, before moving on to Bacone College. There, his quirky mechanics turned him into a 32nd-round Royals draft pick in 2014.

“In those moments, that’s when I knew this is what I’m supposed to be f–king doing, not letting the wind blow me wherever the f–k it goes,” Tim said. “I had a goal. I had things that I wanted to do, things that I wanted to accomplish, and I was making things happen. I found power in that, and I found myself in that.”

Unfortunately, Tim was diagnosed with the same cancer that claimed his father’s life less than a year later. Only 25, Tim remembers having to call his mom following his Stage 3 diagnosis.

“’F–k, I don’t want to tell her this,’” Tim remembers thinking. “I knew it was gonna crush her because she had just dealt with that with my dad seven years before. Calling my mom and my sisters were hard phone calls to make.”

Tim’s colon cancer had already been detected when doctors discovered he had inherited Lynch syndrome, which had gone undiagnosed in Jerry. The condition increases the risk of developing several types of cancer, including colon cancer, and is caused by a genetic mutation.

Once again, I can relate.

I inherited a different mutation from my dad, making me more susceptible to prostate and pancreatic cancer. Thankfully, I have never been diagnosed with cancer, but I do dread having to make the same calls Tim did in the future.

As someone who is predisposed, it was recommended that I start undergoing prostate screenings sooner than men at average risk. I underwent my first a few weeks after my dad died. I intend to repeat the process annually.

Tim, meanwhile, gets a blood test and colonoscopy each offseason. He’s remained cancer-free since his initial battle, which he won following eight months of chemotherapy and tons of help from Kristi, who welcomed Tim into her home after his diagnosis.

Thankfully, neither of Tim’s sisters have Lynch syndrome. “I was the lucky one,” he joked, though he wishes he and his dad had known to test sooner.

“That’s one of the things I feel like maybe fell through the cracks,” Tim said. “I always try to encourage people to get tested.”

Tim has a 50-50 shot of passing Lynch syndrome on to his kids, but he and his partner, Nicole, decided against in vitro fertilization (IVF) before welcoming their first child, Xander, to the world in January.

The procedure would have allowed the couple to conceive a child without the mutation and increased risk of cancer. But Tim said they never really considered the option despite having the means and several conversations about it.

“Which is crazy,” Tim acknowledges on one hand, but he reasoned that he would not have been born had his parents used IVF.

“I didn’t like that idea of playing God with my son because I’m still happy to be here, even if I do have Lynch syndrome,” said Tim, who considers himself a believer, but not all that religious. “And if he has Lynch syndrome, we’ll deal with it. At least we’ll know, and we’ll be ahead of it and watch it.”

Still, Tim struggles with the choice.

“That might be really stupid or whatever. I don’t know if I made the right decision or not. I guess when we test him and he tests ‘nothing,’ then I’ll feel like I made the right decision. But if not, then who knows? Maybe I’ll feel bad about that,” he continued. “I’m just glad he’s here. I don’t really know how it works, but I feel like if I would have done IVF, it would be different. We could have named him the same thing, but I think it would be a different person. I’m happy with the one that I got, so I’d like to actually think he’s perfect. So it’s hard to regret that. I don’t regret anything with that.

“But did I make the right decision? I hope so.”

A few seconds later he adds, “I don’t know. It’s hard. I feel like we made the right decision with that.”

I get the back and forth. The thoughts have crossed my mind too.

* * *

Growing up in the Los Angeles suburbs, Hill always had a hummingbird feeder in his backyard. Jerry loved the little flappers.

Now, whenever Tim and his older sisters see a hummingbird, they think it’s their dad checking in on them. If so, those birds must be impressed, as Jerry always thought his son would play in the majors, even if Tim threw “like a weirdo” from an early age.

“I wish he could have seen that he was right that whole time,” Tim said. “I wish his last memory was where I’m at now. I feel like he would be a lot prouder than where I was at [when he died], and that’s the hardest part for me.”

Tim dwelled on his teenage behavior a few times in our chat, but his dad’s death and the resulting aftermath made him who he is today. The past can’t be changed, but Tim can keep making his dad and his people proud.

That’s been a motivating force for me over the past few months, as I know my dad wanted me to keep living life to the fullest and doing work that I love. He said so in our final conversations.

Tim, much younger than I was when he lost his dad, recalls having a similar heart-to-heart toward the end. “No one’s going to feel sorry for you,” Jerry told him, stressing that Tim had to make something of himself.

It took years for his dad’s advice to kick in, but he still hears those words in his head.

“It took me a while to learn, but I did eventually,” Tim said. “I’m very thankful for that.

“As s–ty as I was for whatever period of time, I was able to come back and bounce back from all that because he did a good job raising me.”

As I reflect this Father’s Day, I’d like to think my dad did the same.