New Yorkers are voting in a Democratic primary likely to pick the city’s next mayor. The incumbent mayor, Eric Adams, is skipping the primary after his indictment led him to plummet in the polls. He announced plans to run in the general election as an independent.

This drama might have been avoided if New Yorkers had been properly taught how to vote in ranked choice elections.

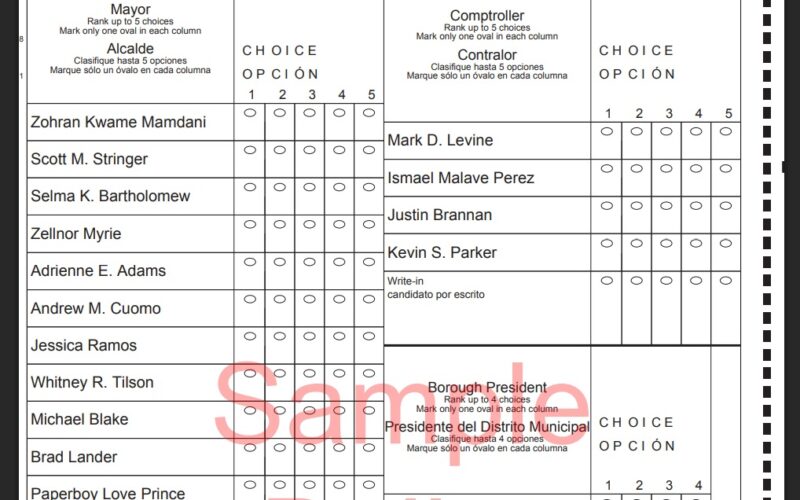

New York City’s ranked choice system allows us to list up to five candidates; if someone we rank highly has too few votes to be competitive, our support shifts to the next candidate on our list. When it was rolled out in 2021, explainers on the mechanism — allowing us to rank our favorite bagels or bodega snacks — aimed to teach New Yorkers how the ranked system worked.

As a professor of economics who researches behavior in mechanisms like ranked choice voting, I was impressed with attempts to educate a city on the voting system. But as a lifelong New Yorker, I wish my neighbors had instead been taught how to use their votes effectively.

Understanding how a system works often matters less than knowing how to use it. Teaching me how a microwave vibrates water molecules to heat my dinner is less helpful than telling me what buttons to press and which containers are microwave-safe.

So how should you use your vote? You should rank five candidates for mayor in your order of preference and you should include some front-runners in your list of five.

Why? Imagine that at the end of ranked choice voting’s elimination rounds, two candidates are left. If you ranked neither, you will sit out the final vote even though you made the effort to go to the polls and cast a ballot. Ranking five candidates and including front-runners gives you a say in who makes it to the final round and who wins.

In 2021, more than 50% of voters in the Democratic primary failed to use all five of their slots and nearly 15% — 140,000 of our friends and neighbors — did not have a say in the race’s final decision.

That primary had 13 candidates, but by Election Day it had more or less solidified around three front-runners: Eric Adams, Kathryn Garcia, and Maya Wiley. Adams received the most first choice votes. As candidates were eliminated, however, Garcia began to catch up. In the final round, she fell short by just 7,197 votes.

When Wiley came in third and was eliminated, her votes split heavily — more than 72% — for Garcia. But more than 74,000 Wiley voters did not rank Adams or Garcia so were silent for the final choice. (Another nearly 66,000 did not rank any of the three so didn’t get a say either). Given how Wiley’s votes split, even a fraction of the 74,000 ranking an additional front-runner could have easily swayed the outcome.

Admittedly, following my advice requires some work. You must learn about candidates beyond your first choice and pay attention to who the front-runners are. Recent polling suggests former Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Assemblymember Zohran Mamdani are likely to be the last two standing, but candidates like Comptroller Brad Lander or Council Speaker Adrienne Adams could take off during the home stretch.

A benefit of ranked choice voting is that you can and should rank whichever candidates you like best at the top of your list, even those unlikely to win. But voting effectively might mean ranking people you don’t love — perhaps even people you actively don’t want to become mayor — later in your list. If you dislike a candidate less than one of the other front-runners, it still makes sense to rank them.

For example, even if you do not want Cuomo to be mayor, if you prefer the former governor to Mamdani, you should still rank Cuomo in your fifth slot. (Similarly, even if you strongly dislike Mamdani, you should still rank him fifth if you prefer him to Cuomo).

Fail to follow this advice and you could end up like the Wiley voters who did not weigh in on Garcia versus Adams. If they had better understood how to use their votes, we might have been facing a boring primary ushering Kathryn Garcia into her second term. Instead, the primary is hotly contested, so you’ll need to do some research — and possibly hold your nose as you fill in your ballot — to ensure your vote counts.

Kessler is a professor of economics at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. His book, “Lucky by Design: The Hidden Economics You Need to Get More of What You Want,” will be published in October by Little, Brown Spark.