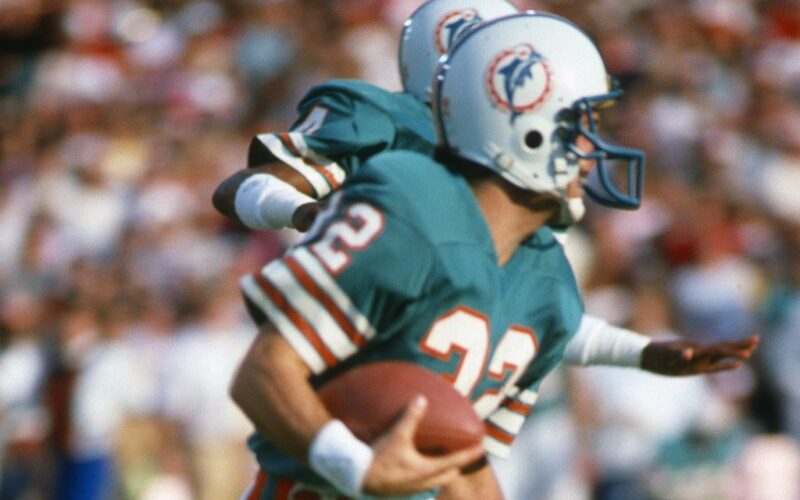

He was not a household name. But if you followed the NFL in the early 80s you knew the name Tommy Vigorito.

He was a Parade All-America school-boy legend out of North Jersey, packing them in as his small Catholic school battled teams in one of the state’s most revered conferences. It was before the parochial schools went crazy, and broke away, with their national scheduling and their own version of free agency (recruiting transfers) after every season. He drew them from small towns from Sparta to Pompton Lakes. It was high school football by Norman Rockwell.

He became a star at UVA and the subject of a bidding war when the Montreal Alouettes of the CFL went head-to-head with the Miami Dolphins for his talents. In many ways it was the first indication that the money would explode when, in fact, there was unfettered competition for a player’s services.

And he was always worthy of — in coachspeak — the ultimate compliment. He was a player.

He became the first rookie since Gale Sayers to score a touchdown three different ways — kick return, reception, run from scrimmage. His 87-yard punt return for a touchdown against the Pittsburgh Steelers on one of ABC’s first “Thursday Night Football” telecasts in 1981 quickly became a Howard Cosell classic call.

Don Shula loved him, and he was a key impetus for the Hall of Fame coach to abandon pound and ground football and to embrace airing it out — creating coverage match-up nightmares. That, and the drafting of Dan Marino.

He suffered one the worst knee injuries ever seen by the Dolphins medical staff in the opening game of his third season, at the end of another of his patented long punt returns — a 62 yarder against the Bills in Buffalo.

His career ended not long after. He went on to become a VP on Wall Street and lent his name to many philanthropic causes along the way.

This past May he died almost certainly from the ravages of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) after several years of physical and mental misery. No one from the NFL offices made the 18-mile trip to North Jersey to attend his memorial services, even after being personally invited. Tommy Vigorito was 65-years-old.

Monday, a crazed gunman attacked the office building housing the NFL with an AR-15 assault rifle, killing four, among them a heroic member of the NYPD. The killer failed to enter the NFL offices but carried with him a handwritten note saying the cause of his actions was CTE. Then he put a fatal round in his own chest, leaving his brain whole, to be examined — the only way CTE can be unequivocally proven.

Immediately the football PR machine began to spin — putting it out there that the killer never played pro or college football, only high school. Was the killer just a lunatic? In so doing, Pandora’s Box has been sprung wide open.

As Vigorito’s agent, I saw every one of his NFL games — there were stretches of them — some because of his elusiveness — where he was never tackled. The brain abuse he experienced occurred way before his time in the NFL. High school football, then college, certainly took their toll.

And I can tell you some of the hardest hits I ever took carrying a football, in a career that went as far as serious major college competition, happened in grade school. You don’t forget getting your bell rung.

CTE has no timeline, no boundaries. I spent his NFL draft day with Chicago Bear Dave Duerson, an NFL disability board member and CTE victim who fell to his own gun. I saw firsthand the volatility of eventual CTE suicide victim Andre Waters, almost coming to blows with him in the locker room in the early 90s. Monday’s crazed killer referenced former Steeler Terry Long, a CTE victim who killed himself by downing antifreeze.

The killer was born 14 years after Vigorito last touched a football in the NFL. He was denied access to the NFL’s inner sanctum. But the vilest killer was already there. Football head injuries have produced a conga line of punchdrunk Beau Jacks. A majority of these cases, especially those who played in the 80s and 90s, are hitting the league and beyond like a tidal wave.

The battle versus CTE — from people like Chris Nowinski of Boston University’s Concussion Legacy Foundation and others like him — must be uncompromisingly supported and embraced across every platform of football if this tide is to be stemmed.

We can wait no longer.

Marotta is a filmmaker and writer.