The tragic mass shooting in Manhattan last week has reignited a conversation that demands urgent attention concerning the prevalence of brain injuries and their impact on public health and public safety.

A week ago today, a gunman identified as Shane Devon Tamura opened fire in a Midtown office building, where the NFL headquarters is also located. He killed four individuals — NYPD Officer Didarul Islam, Blackstone executive Wesley LePatner, security officer Aland Etienne and Rudin real estate associate Julia Hyman — before taking his own life.

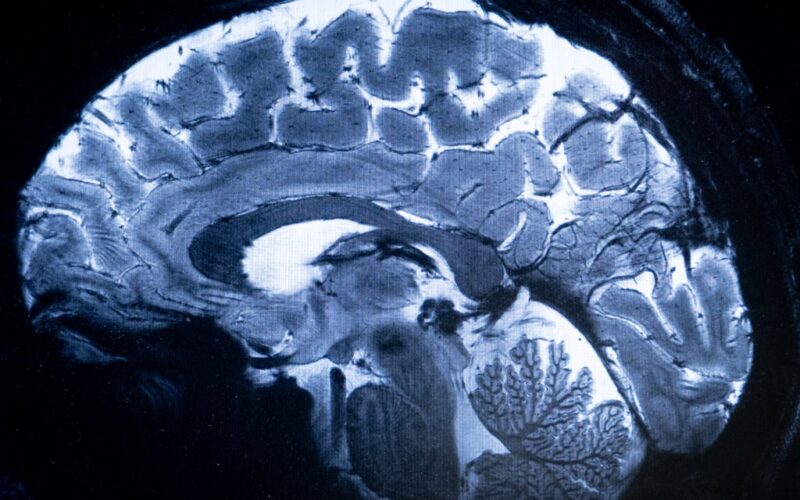

The suspect reportedly carried a note claiming he suffered from CTE — chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a type of brain injury caused by repetitive head trauma — and blamed the NFL, stating: “Study my brain please. I’m sorry.”

Although Tamura did not play in the NFL — only high school football — but if he was battling CTE, it highlights the predictable — and increasingly visible — intersection of untreated trauma, undiagnosed brain injury and inadequate systems of care. Whether in professional sports, the military or civilian life, we’ve seen too many lives shattered by the consequences of brain injury and mental health conditions left unaddressed.

We owe it to those lost — to those at risk and to public safety — to act on what we already know.

Each year in the U.S., tens of thousands of people live with the effects of traumatic brain injury (TBI), a leading cause of injury-related death and disability. In 2021, the U.S. had approximately 69,473 TBI-related deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, equivalent to about 190 deaths per day — and more than 214,000 hospitalizations in 2020 alone.

Among military populations, the burden is similarly high: more than 450,000 U.S. service members received a TBI diagnosis between 2000 and 2021, most cases classified as mild but contributing substantial long-term impacts.

Early and frequent screening must become the standard, not the exception. Traumatic brain injury and mental health conditions often coexist in complex and compounding ways.

Symptoms like irritability, impulsivity, memory loss and mood swings can overlap and worsen if left untreated. And mounting evidence points to a strong connection between TBI and suicidal ideation, making this a public health issue that cannot be ignored.

Yet today, we lack a standardized national framework for TBI assessment.

Current approaches to classification, screening data collection, short- and long-term care, prevention and rehabilitation remain fragmented across systems. This patchwork results in missed opportunities for early identification, inconsistent care and underinvestment in solutions that work.

A national TBI protocol would complement tools like the Columbia Protocol, an evidence-based method for identifying suicide risk. Together, these tools could offer a powerful, integrated approach for high-risk populations: athletes, veterans, military service members, first responders and others exposed to repetitive trauma.

But screening alone isn’t enough. What follows must be accessible, sustained and grounded in evidence-based practices tailored to individual needs. Too often, systems default to siloed or one-time assessments — missing the evolving nature of both brain injury and mental health conditions.

Public and private research partnerships must be outcome-driven, data-informed and held accountable for real-world impact. There are promising examples, such as the Department of Defense’s collaborations to study the effects of blast waves on the brain or the NFL’s investment in concussion protocols. But funding alone isn’t impact. Research must move beyond academic journals and into clinical care.

To make that happen, researchers, clinicians, policymakers and advocates need access to high-quality, anonymized data. We can’t solve a problem we can’t see.

Finally, we must focus on practices that prevent these tragedies. That means supporting efforts to catch issues early, embedding mental health care into primary and emergency systems and supporting families and caregivers long before crisis strikes.

The Manhattan murders are unforgivable, with families now forever impacted because of them. If CTE did play a role, the killer’s request to “study my brain” should spark robust discussion about how this could have been prevented.

Let this moment serve not only as an occasion for mourning — but as a catalyst for systemic change. The human cost is too high to ignore.

Franklin is a nationally recognized leader in behavioral health. Over a distinguished 25-year federal career, she served as a senior executive in both the Department of Defense and the Department of Veterans Affairs leading suicide prevention efforts. Larkin, a former Navy SEAL, 40th U.S. Senate sergeant at arms and father of a Navy SEAL son who died by suicide, is chief operating officer of Troops First Foundation and chairman of Warrior Call.