Strange as it may seem, there was a time when mothers thought it was fine to go shopping and leave their babies alone in carriages on New York City streets.

The New York Tribune noted that some businesses supported this practice by hiring curbside babysitters, often a “motherly gray-haired woman” to watch the baby buggies.

When the mothers returned with their packages, they were usually greeted by smiling little faces and happy gurgles.

But on July 29, 1919, Mrs. Elsa Wentz returned to an empty carriage.

Arthur Philip, her 7-month-old blue-eyed boy, was gone.

When Wentz arrived, the store’s designated carriage area was jammed. So she wheeled around to the side of the building where several other buggies were parked. No matron was posted there, but it still seemed safe, even though another baby snatching had happened a couple of months earlier in the same neighborhood.

On May 23, Olva Koskinen, 6 weeks old, vanished from his carriage as his mother, Anne, shopped in a dry goods store.

No ransom demands appeared, so police assumed they were looking for a childless woman driven by a desire to have a baby. Their hunch was right.

Within a week, a woman living on E. 130th St. reported hearing an infant wailing in an apartment occupied by a young widow, Carmela Marzano. The kidnapper tearfully confessed.

“My longing for a baby to love blinded me to the sorrow of the mother I was robbing,” she told a judge during a hearing.

Personal tragedy had spurred Marzano’s crime. A few months earlier, her husband died of wounds suffered on a WWI battlefield in France. Before that, the couple’s own baby, a little girl, died at 4 months old.

“Mother mania” was how police characterized her mental state. The Koskinen baby was reunited with his mother, and Marzano went to a reformatory.

Hope for a similar easy resolution for the Wentz family quickly faded. A week after Arthur disappeared, a ransom note was delivered to their home, written in a feminine hand and demanding $100 for his safe return.

In the letter, the buggy robber explained that she had wanted to raise the baby as her own, but he cried so much that she now wanted to return him.

Accompanied by a detective, the baby’s father, August, brought a decoy envelope to a street corner chosen for the ransom drop. But no one came to collect the money.

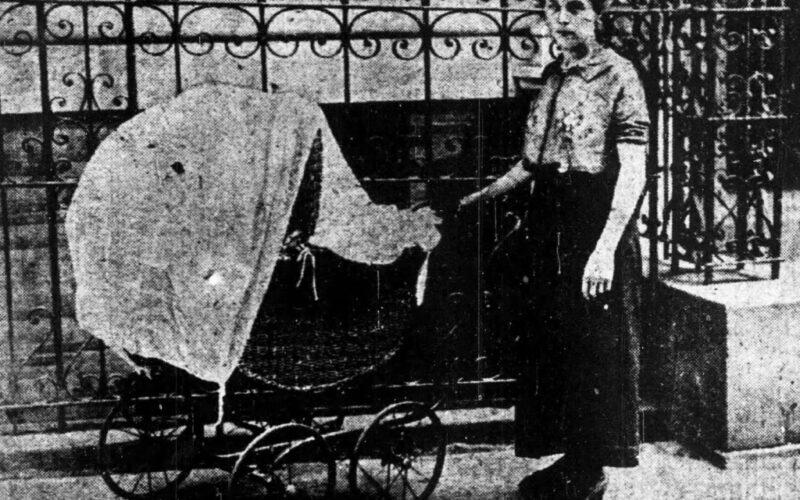

For several days, the carriage remained parked in front of the store in the hope that the kidnapper would return the child. But it remained empty, even after Elsa, who grew more desperate every day, pinned a note on it: “Whoever you are, you are breaking my heart. Please bring back my baby.”

Elsa brought in a spiritualist, who assured her that her boy was well cared for and that he was somewhere close. The seer narrowed down the location to a place near or over a garage in Brooklyn, Manhattan, or the Bronx.

There were grim meetings with every male foundling who landed on the streets or showed up at city hospitals. Even worse were trips to the morgue, where the couple viewed the tiny corpses of lost boys. Elsa would faint after each encounter.

“I do not care if they never know who did it. I only want my baby,” Elsa told the Daily News.

In December, a stranger approached a police officer in Grand Central Terminal. The man asked the officer to hold his baby for a few minutes while he took care of something.

Then he dashed away and never came back.

A note pinned inside the child’s cap read:

“For the Love of Mike, Somebody take this kid. He is one too much for the family. Give him to Nelly Bly of the New York Journal. He is 7 months old and as healthy as they make ’em. Can’t afford him at the price they are charging for milk today. There are others I am trying to support.”

Journalist Bly had long championed the downtrodden, especially women, children, and orphans. Now in her 50s, she helped poor families whenever she could.

She offered to adopt “Love o’ Mike,” which was how newspapers started referring to the child.

But before Bly could finish the adoption paperwork, she got word from Bellevue, where Love o’ Mike was being held, that his parents — Elsa and August Wentz —had positively identified him as their Arthur.

The hospital said the boy was already back at the Wentz home, where Christmas preparations were underway.

It seemed like there would be a happy ending to this kidnapping, but then Lena Lisa, a widow who supported her family by making artificial flowers, came forth.

Lisa declared herself Love o’ Mike’s mother and admitted she had given him up. Her story was that she could not make ends meet on the money she earned selling flowers. In desperation, she asked a neighbor to bring the younger of her two sons, Enrico, to Bly, hoping the famous writer could help find him a better home. But the neighbor lost his nerve and instead dumped the boy with a cop.

When she read in the newspapers that her son had gone to another poor couple, Lisa decided to reclaim him.

The child’s joy upon seeing Lisa was all that authorities needed to believe he was her child. Even Elsa Wentz, though heartbroken, could not deny it. Bly promised to help Lisa find a better way to support her family.

“I must keep my baby’s clothing clean and ready for him,” Wentz told reporters as Lisa took Enrico home. “I shall never give up hope.”

Arthur Philip Wentz was never found.

Originally Published: