David Bowie’s had a vigorous afterlife since dying in New York 10 years ago.

He conquered Billboard’s album chart for the first time in his career with the dark jazzy masterpiece “Blackstar,” released Jan. 8, 2016 — just two days before his death.

His best-known singles surged back into the top 100 on both sides of the Atlantic as well. And in the decade since, his record company has kept Bowie’s name hard at work, with box sets, live discs, archival releases, rarities, remixes and reissues pouring forth every year.

“At the record company meeting / On their hands, a dead star / And oh, the plans they weave / And oh, the sickening greed,” sang Morrissey, one of the many other rock gods Bowie inspired, in the 1980s.

But Bowie himself — a shrewd businessman who once sold bonds backed by the rights to his music — planned out the exploitation of his catalog before his death.

He was King Tutankhamun leaving instructions for plundering the treasures from his own tomb.

Bowie’s not just of archaeological interest in 2026, though.

He’s in the records, and the headlines, made by today’s acts, too: in the gender-bending themes and affected identities of a Chappell Roan, for example.

Though as Miss Roan’s sudden renunciation of another 20th-century icon, Brigitte Bardot, suggests, today’s stars don’t necessarily know anything about those who came before.

Bardot, who died last week, was a sex symbol, feminist, animal-rights activist but also, to Roan’s dismay, a staunch supporter of the French hard right and opponent of Muslim migration.

Is there a side of Bowie, too, that those who celebrate him as a queer pioneer might be shocked to discover?

There are two, actually.

The first is that this bisexual alien from Mars turned out to be a family man — when he got the chance to leave the hedonistic lifestyle he’d explored and chronicled throughout the 1970s, he took it and never looked back.

He left the stage, never to return to touring, in 2004 after suffering a heart attack.

But it wasn’t only health that kept him off the road: He wanted to be around as a father to the daughter he had with his supermodel wife, Iman, in 2000.

They were an extraordinary family in obvious ways — but they were also the Joneses.

The real Bowie, before he took a stage name, was an Englishman named David Jones, born into a middle-class family on Jan. 8, 1947.

Perhaps he wound up not being such a revolutionary misfit after all, but wasn’t he the real thing back in the ’70s?

Yes, he was — but that’s the other side of Bowie his progressive admirers may find a poor fit for their expectations because the radical Bowie was distinctly Nietzschean: more Bronze Age Pervert than Chappell Roan.

When he sang “gotta make way for the Homo superior” in his 1971 hit “Oh! You Pretty Things,” he wasn’t just making a gay pun — though that’s there — nor alluding to Olaf Stapledon’s 1935 sci-novel about the next step in evolution beyond Homo sapiens, though he was doing that, too.

He was also continuing to explore an Übermensch theme alluded to by a track like “The Supermen” on his album of a year before, “The Man Who Sold the World.”

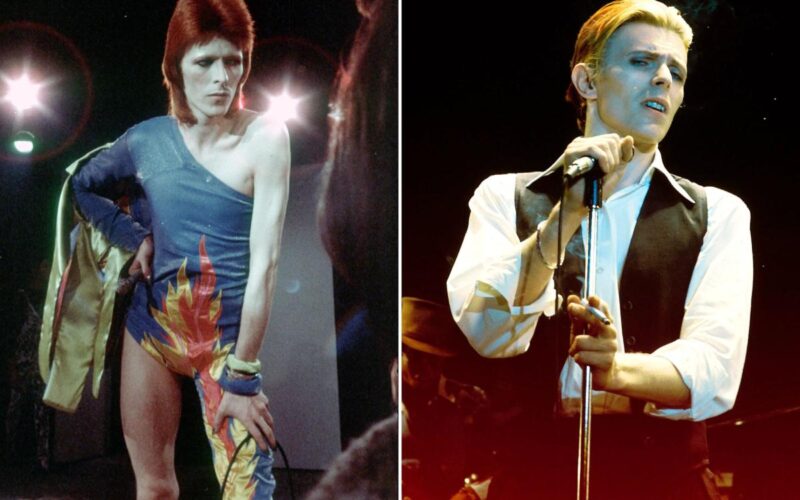

Bowie would often be accused of dabbling in right-wing ideology, especially with the “Thin White Duke” persona he adopted on tour following his 1976 album, “Station to Station.”

He did more than dabble at times — in 1975 he told one interviewer, “I believe Britain could benefit from a fascist leader. After all, fascism is really nationalism.”

The next year, he told Cameron Crowe in a Playboy interview, “I believe very strongly in fascism. The only way we can speed up the sort of liberalism that’s hanging foul in the air at the moment is to speed up the progress of a right-wing, totally dictatorial tyranny and get it over as fast as possible.”

He added, “Rock stars are fascists, too. Adolf Hitler was one of the first rock stars.”

Yet James Rovira, editor of the book “David Bowie and Romanticism,” which includes a chapter looking at Bowie’s provocative remarks from this period, notes Crowe had reason not to take Bowie at face value.

Asked “Do you believe and stand by everything you’ve said?” Bowie replied “Everything but the inflammatory remarks.”

Crowe concluded he was “a sensational quote machine. The more shocking the revelation, from his homosexual encounters to his fascist leanings, the wider the grin. He knows exactly what interviewers consider good copy; and he gives them precisely that.”

Bowie was also, by his own account, out of his mind in those years, plunged into paranoia by cocaine and cabalism, his marriage collapsing, going through an equally difficult divorce from his management.

You know things are bad when you turn to Iggy Pop to help you get your head straight in Cold War Berlin.

Bowie’s late ’70s European sojourn would produce five classic albums, however — two by Pop (“The Idiot” and “Lust for Life”), three by Bowie (“Low,” “‘Heroes’” and “Lodger”).

What makes Bowie of lasting interest — 10 years after his death and for tens to come from now — is not the caricature of him as a pinup of liberal liberation but the story his albums document of how he turned from Nietzschean radical, if not fascist, to the most surprisingly well-adjusted and family-oriented of celebrities.

Those albums of the late ’70s, and his 1980 masterwork “Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps)” tell the tale.

After that came his commercial zenith — and critical nadir.

The ’80s weren’t easy on Bowie, even though he’d sobered up and started insisting he was never gay or bi after all.

And he sold a lot of records, beginning with “Let’s Dance” in 1983, which shifted about 10 million copies worldwide.

His follow-up, 1984’s “Tonight,” also went platinum. But by the time of “Never Let Me Down” in 1987, the critical consensus held that Bowie was washed up.

Solving the problems, personal and philosophical, that had plagued him in the 1970s seemed to have deprived him of what made him a great artist.

Was Bowie already creatively dead 30 years before cancer killed him?

Most of his 1990s and early 2000s albums were damned by the same faint praise, as “his best album since ‘Scary Monsters’” — meaning he wasn’t making any progress, even if he stopped slipping further behind.

Yet the post-1980 Bowie is worth listening to and not just for “Blackstar,” a new book on his later years argues.

“Lazarus: The Second Coming of David Bowie,” by Alexander Larman, hits shelves Feb. 24 and makes the strongest case yet that Bowie’s story remains compelling to the end.

“He is still the biggest, coolest cult rock star there ever was, and the passing of time since his death has done nothing to diminish his standing,” says Larman, who was not, however, a fan from the first.

“Growing up, I wasn’t all that interested in Bowie,” admits the 44-year-old author.

Back in the “late eighties through to the late nineties,” he says, Bowie “seemed like a slightly desperate and pathetic figure — Sting with a bit of residual menace, maybe.”

But Larman, today the literary editor of The Spectator World, took a chance on Bowie’s 1999 album, “Hours” — not generally regarded today as one of the best even among Bowie’s later works — which led to “a deep dive into the back catalogue.”

“And oh my, it was revelatory. I became completely obsessed by him and have been for the past 25 years or so.”

There are Bowie biographies aplenty already, such as David Buckley’s “Strange Fascination” and Christopher Sandford’s “Bowie: Loving the Alien,” as well as volumes looking at his total output, like Nicholas Pegg’s “The Complete David Bowie.”

Larman tackles the task of showing how great the late Bowie, specifically, was — the worth of works like “The Buddha of Suburbia,” “Outside” and “Hours,” as well as his well-rated comeback albums (after his 2004 retirement from touring) “The Next Day” and “Blackstar.”

“It seemed to me that the only real untold story was the second half of the life and career, which had a beautifully simple structure to it — he’d flopped, he was trying to recapture the old glories, this didn’t work, he did some clever things and some silly things and was overpraised and underrated, then he played Glastonbury in 2000 and everyone loved him again,” at least in his native Britain.

“And of course the rest of the narrative is proper epic stuff — near-death experiences, a rise from the grave (hence the title) to produce two final masterpieces and then a definitive death soundtracked by ‘Blackstar.’ ”

Americans may find their perception of Bowie’s reputational fortunes differs a bit from Larman’s Anglocentric point of view — not his Glastonbury Festival performance in 2000, but the endorsement of younger bands like Nirvana and Nine Inch Nails put Bowie permanently in the pantheon of cool over here by the mid-1990s.

That was almost a Pyrrhic victory for him, though — his 1995 album “Outside,” actually an eclectic marvel, was dismissed by many as a leap onto the Trent Reznor bandwagon.

His 1997 album, “Earthling,” really was an attempt to catch up to the latest trend, “drum and bass” electronica.

His 1993 album “Black Tie, White Noise” was a miss, and so was his 2004 album “Reality.”

But at his best moments on “Outside,” “Hours,” “Heathen” and the curious soundtrack-inspired 1993 album “The Buddha of Suburbia,” Bowie was fully Bowie, even before the final triumphs of “The Next Day” and “Blackstar.”

They’re not happy or reassuring albums, packed as they are with meditations on religion, violence, aging and death, alongside callbacks to the science-fiction themes of his earlier career.

But they’re mature reflections of a man who’d come out the other side of the last century’s madness — and didn’t flinch from the horror unleashed this century on the city he adopted as his home.

“As far as I can make out, he felt far more embedded in New York life after 9/11,” Larman tells me.

“Throughout the ’90s, he liked the idea of flirting with Britishness — he would curry favor with journalists by suggesting that he’d move back to London one day, which he never did — but when he was having his decade-long ‘retirement,’ he was far more active in New York cultural circles than he had been before.”

He sang at the end, on “Blackstar’s” most elegiac cut, “Dollar Days,” of “the English evergreens I’m running to.”

He was an alien who never lost his love of home, wherever he or it was.

Daniel McCarthy is the editor of Modern Age: A Conservative Review.