“Remediation manager” sounds more like a third-rank bureaucrat or elementary school reading specialist than a revolutionary figure. But Manhattan Federal Judge Laura Taylor Swain’s order Tuesday kicking off the process to appoint such a manager marks a turning point in the horrific history of the city’s jails because of the potent powers of the position.

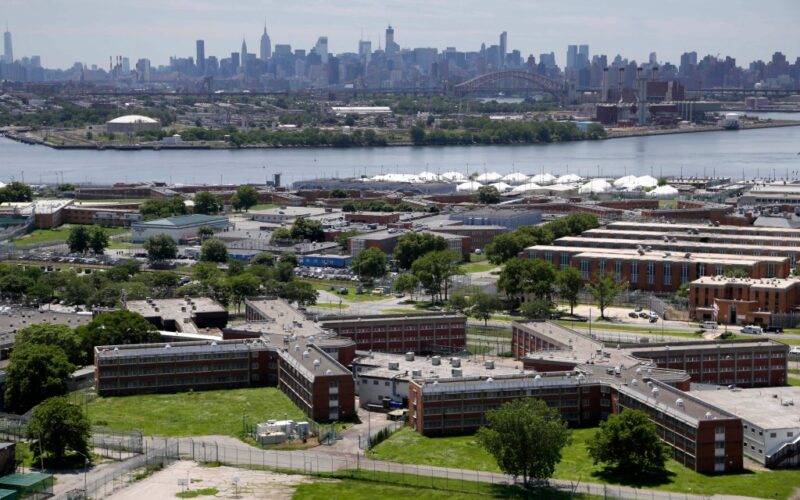

For 10 years, Swain has overseen the federal consent decree that the city signed agreeing to address the then-unconstitutional levels of violence in the jails. But things have gotten worse, not better. Today, violence so dwarfs the 2015 state of affairs that returning even to those unconstitutional levels seems like a far off dream.

Can any one person fix the sprawling problems of Rikers? And does the judge’s order provide the right structure and powers to ensure the “remediation manager” can negotiate the politics of the jails and the city to meet constitutional muster? The answer is far from clear, but the broad powers and the independence of the position offer the last, best option to fix an entrenched problem of long duration.

The “manager,” more commonly known in the law as a “receiver,” is a rarely used and powerful remedy that — colloquially, but also as a matter of law — is intended as a last resort. To impose one, a court must show primarily that there is the presence of grave and immediate harm, that nothing short of a receiver will work, and that it is futile to continue to insist on compliance with court orders.

A receiver stands in the shoes of the executive — appointing and dismissing personnel, setting budgets and remaking organization charts, even if laws need to be changed and collective bargaining agreements altered. But unlike an executive appointee, the receiver retains its independence because it is appointed by and reports only to the court.

And critically, since he or she is intended to be in place until the problem is fixed, the receiver can operate, as a judge does, protected from the political pressures attendant on appointed positions of limited tenure.

These features of tenure may not guarantee insulation from the day-to-day buffeting an executive or elected official faces — nothing can do that. But it provides as much room as is possible for a receiver to hold onto the single goal to tend to the well-being of those who live and work in the jails — in this case, the reining in of violence to constitutional standards.

It’s not hard to see that part of the reason that courts are chary of imposing this remedy is that it skates in a potentially slippery area between the limits of executive and judicial powers. And it is possible that in this case, the modest name of the position (and unusually, the retention of a commissioner as well as the appointment of the receiver) is a Solomonic gesture to the city, wounded at the stripping of its authority.

The history of violence, and the particularly gruesome nature of the record 38 deaths in this mayoralty tell the story of the long and structural failure of the jails: officers watching as an incarcerated person bleeds out after slitting his own throat with a razor; a captain joking as an incarcerated person hangs himself in front of her; a person choking to death on an orange in an unstaffed unit, as others in the unit bang on the glass for help.

Each of these incidents is connected to the failure of management, organization and accountability, and fixing those failures requires, as the monitor has noted, the remaking of the agency.

Yet today, accountability for brutality is a joke. Indeed, one deputy commissioner finally “resigned” last year on the heels of scandals that he had sold settlements cheap in violence cases. The management system became so broken that at one point a third of the staff wasn’t coming to work; triple shifts were the norm, leading to exhaustion and violence. This is a conundrum because the city’s jails are one of the most richly staffed in the country or, as the court put it, “overstaffed and underserved.”

The lethal ineptitude has been accompanied by contumacious recalcitrance that has ranged from the comic (the failure even now after 10 years to produce an organizational chart of the agency) to the deadly (the failure to produce guidance to officers about how, when and the extent to which they may use force, the motivating and enduring complaint of the suit that led to the consent decree).

And finally, what was fatal to city control, the failure to abide by three remedial orders, in addition to the failure to meet the requirements of an “Action Plan” that the city itself devised— all leading to findings of contempt.

The incapacity of the agency has also been laced with corruption. The penultimate commissioner, Louis Molina, engaged in an unparalleled campaign of mendacity, with the most egregious incident first hiding from the court-appointed monitor a set of life-altering injuries and two deaths suffered by five incarcerated people, and then defiantly claiming that he had no obligation to report these events once they were uncovered.

On Rikers, a thicket of laws and lore, regulations and culture bind and barnacle decision-making. The journal Vital City detailed how the organization has been shaped or misshaped through a thousand different deals and handshakes that affect how jobs are handed out, who staffs the most challenging units, when breaks are taken, who gets promoted, who gets disciplined, all of which contribute to the chaos and violence of the institution. The role of the unions in all this is prickly, powerful and not always benign.

In the face of these structural and political problems, what can the remediation manager do? Plenty.

The tenure and independence of the position will end the start-and-stop and redirection that has been fatal to so many of the jails’ plans to improve conditions. And the broad powers the court has conferred to “control, oversee, supervise and direct all administrative, personnel, financial accounting, contracting, legal and other operational functions” will be essential to fix some of the structural issues that have bedeviled the jails.

Although unusually the court has permitted the Correction commissioner to remain alongside the manager, “the manager shall have the authority to direct the commissioner” to take the steps necessary to effect the course of action determined by the manager. This is a potential trouble spot.

The court’s order appears to confer broad authority on the manager, with the commissioner playing a subsidiary role. But the devil is in the details and the operations: What really belongs to the manager and what to the commissioner, and how cumbersome will it be to move swiftly and effectively with this structure?

Success will depend entirely on who the receiver is, a choice the court will make after the parties provide a list of candidates at the end of August. The receiver will need to be a person of consummate skill, enormous experience and indisputable gravitas. Although he or she cannot be political, the receiver must have the ability to navigate the political landscape, to negotiate with the unions and the administration and to move with alacrity and effectiveness.

The receiver has great power, and he or she needs to build a structure that is remade with the participation of the city so that it will endure and the city can run it when the agency returns to its supervision. That is a steep hill.

It is hard to remember a time when the city’s jails have not labored under a consent decree. The court notes six decrees alone that were meant to cure the problems of “excessive force,” the legal nicety that defines the grotesque levels of violence. Through all of these efforts, the city’s response might be summed up in the schoolyard taunt: “Make me.”

We will now see whether a receiver, or a remedial manager, can indeed remake the jails.

Glazer is the founder of Vital City, where this first appeared. She has previously served as a federal prosecutor and as the criminal justice adviser to a New York governor and New York City mayor.