Black American music is music of the spirit, a profound diversity of lessons to be enjoyed. Never duplicated but often imitated, its drumbeats are heartbeats of the inner person that ignites American culture and beyond.

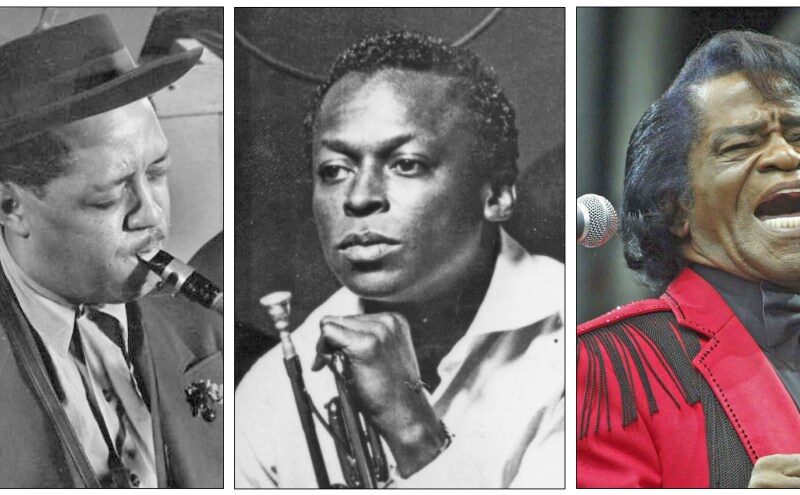

Just reflect for a minute what American music would sound like without this organic pollination of artists: Michael Jackson, James Brown, Bud Powell, Louis Armstrong, Charles Mingus, Prince, Nina Simone, Max Roach, Charlie Parker, Mahalia Jackson, W.C. Handy, B.B. King, Charlie Pride, Beyonce, Little Anthony and the Imperials, Quincy Jones, James Reese Europe, Roy Haynes, Gregory Porter, Henry Threadgill, Sun Ra, Sonny Rollins, Warren Smith, Beyonce, Snoop Dogg and Kendrick Lamar.

The great pianist and composer Randy Weston informed me that everything the ancestors did was musically oriented, from ceremonial dances to religious rituals. These tribal African dances are reflected in modern dance (Alvin Ailey, Katherine Dunham, Camille A. Brown and Savion Glover), breakdancing and swing (1930s-early ’40s), which gained recognition at Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom.

Young black teenagers originally danced the Lindy Hop on the streets of Harlem for money, similar to breakdancing in the 1980s. White teenagers across America did the Lindy Hop on TV dance shows such as Dick Clark’s “American Bandstand.”In the 1920s, a great mass of white Americans began doing a West African (Ashanti) dance they called “The Charleston.”

The Savoy’s regular “Battle of the Bands” welcomed clarinetist Benny Goodman and His Orchestra competing against Chick Webb. Of course, the drummer won. Goodman was hailed as the “King of Swing.”

How ridiculous it was that Webb, Count Basie and Fletcher Henderson were swinging harder than Goodman in their sleep. Amiri Baraka wrote in a haiku, “If Elvis is King, then James Brown must be God,” which speaks to the lunacy of such titles. It was noted during an interview with the doo-wop singer Joe Rivers that Elvis Presley occasionally sat in the Apollo Theater’s balcony, checking out the dance steps of whoever was performing.

The great trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie noted that the Apollo Theater balcony was notorious for whites appropriating Black music forms. “Sometimes from the stage, I could see them up there copying down our music note for note,” said Gillespie. “To be honest, that’s why coming up with bebop was so great — they couldn’t copy it; damn near didn’t even understand it.” Like avant gardism or creative music without boundaries, the complex rhythm grooves reflect the outer galaxy of the song “Ob-La-Di,” where all blues is pure hipness.

It wasn’t just the contribution of music but an entire cultural experience; a unique style of dress — from Stacy Adams shoes to berets and fedoras with a Harlem block, Lester Young’s pork pie hat, silk suits, dark glasses, and the fine silk dresses and hats worn by Lena Horne, Billie Holiday, Eartha Kitt and Nancy Wilson. And of course that hip vernacular: “Give me five, daddio,” “What’s happening, baby? Ain’t nothin’ but the rent,” “that outfit is bad.” The vernacular and dress style, like the music, will continue to change and influence the world and America’s contemporary culture.

The banja or banjo was originally an African instrument that was made and played by enslaved blacks on Southern plantations. It later became a popular American instrument, along with the djembe, kora, and the kalimba (a hand-held African thumb piano instrument played by Maurice White of Earth, Wind and Fire). Percussionist Chief Baba Neil Clarke, saxophonist T.K. Blue and trombonist Craig Harris now use some of these instruments.

Long before CBS’ “60 Minutes” featured the Gnawa musicians, Weston was one of the first artists to bring Gnawa musicians of Morocco into his band (Gnawa music developed through the cultural fusion of West Africans brought to Morocco).

Samuel A. Floyd Jr.’s book “The Power of Black Music: Interpreting its History from Africa to the United States” (Oxford University Press, 1995) connects the origins of African music to slave culture and shout worship to the Harlem Renaissance, Negro spirituals, concert halls, classical composer William Grant Still, Miles Davis and Ornette Coleman. The fundamental elements of African American music were the sounds of enslaved Africans; cries, hollers, call and response, additive rhythms, bent notes, hand-clapping, stomps and constant repetition of rhythmic and melodic phrasing (from which riffs and vamps were derived).

Hip hop just celebrated its 50th anniversary. These artists bum-rushed the entire industry — from blazing defiant lyrics to becoming record mogul millionaires in corporate boardrooms; baggy jeans, baseball caps, leather sneakers and hoodies became a billion-dollar market.

The sound of Black American music influenced Cuban trumpeter and bandleader Mario Bauza while he was in his homeland, but upon arriving in New York City, he quickly introduced Cuban music with its unique styles to the city scene. His introduction of his fellow countryman singer and percussionist Chano Pozo to Dizzy Gillespie led the two to write “Manteca” and “Tin Tin Deo,” combining the trap drum set and congas.

The Latin jazz and jazz tradition has blossomed with percussionist and composer Bobby Sanabria, who is of Puerto Rican descent, along with Arturo O’Farrell, David Virelles, Melvis Santa, Carlos Henriques, and Omar Sosa, who fuses Afro Cuban jazz, blues and Santeria chants. “The oral tradition is meant to be experienced,” said singer, dancer and pianist Melvis Santa.

While the baritone Paul Robeson, the contralto Marian Anderson and the soprano Leontyne Price were quietly inspiring generations of opera singers around the world, it took 138 years of non-inclusion before the Metropolitan Opera introduced its first opera written by a black composer, trumpeter Terence Blanchard, “Fire Shut Up in My Bones,” 2021. His music was saturated with the blues, jazz, foot-stomping soul and classical music.