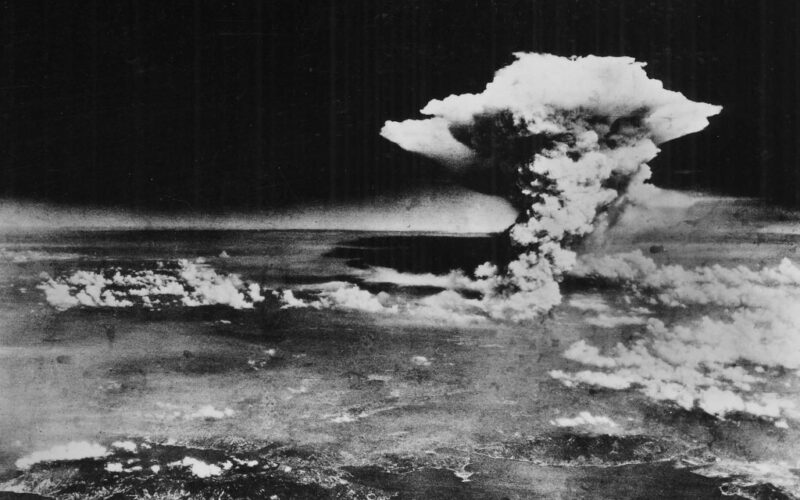

In war, the deaths of civilians and combatants are unfortunately inevitable. Today, 80 years after the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and on Nagasaki, debate still continues over their use, which resulted in an unprecedented number of deaths, destruction, and long-term health effects on survivors.

When President Harry S. Truman faced the most difficult decision anyone has had to make in the history of the world, he was confronted by these facts:

- Japanese troops had almost always fought to the last man, which resulted in more American casualties than if those defeated troops had just surrendered and become POWs.

- Beginning on Oct. 25, 1944, Japanese kamikaze suicide pilots began a new aerial tactic by directly flying their planes into American ships with the hopes of causing extensive American losses in both personnel and ships.

- During the 1945 battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa, which were the closest American ground forces had gotten to the Japanese home islands, American casualties were far higher than those sustained in other battles against Japan.

On March 9/10, hundreds of American B-29 bombers dropped enough incendiary bombs to kill an estimated 100,000 residents of Tokyo and destroy enough buildings that left approximately one million people homeless. Soon thereafter, other Japanese cities were subjected to similar deadly B-29 fire-bomb attacks.

But even after extensive losses of its citizens and infrastructure from these bombing raids, Japan had not yet sued for peace. Truman’s military advisors estimated that a ground invasion of Japan would result in a catastrophic number of American casualties and subsequently ordered more than a million Purple Heart medals.

Finally, there was the matter of American hatred for Japanese, which included members of Japan’s military as well as Japanese-American citizens and legal non-citizen residents. By 1945, anti-Japanese prejudice was completely ingrained in the American psyche.

In the late 1800s, Japanese migrants began moving to the United States. Anti-Japanese prejudice, along with existing anti-Chinese prejudice and anti-Chinese immigration laws, ensured that by the early 1900s, further Japanese immigration would be severely restricted. By law, Japanese immigrants couldn’t become naturalized citizens, but their American-born children could.

For decades, Japanese-Americans faced extreme prejudice which resulted in a 1942 military order for all those of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast, citizen or not, to be interned in American concentration camps. During World War II, America was also fighting Germany and Italy, but during the war, far fewer German and Italian non-citizen immigrants were interned than Japanese and those who were interned had been carefully vetted by the FBI as being sympathetic to their former homelands.

Hatred for the Japanese Empire emanated from the multiple Dec. 7, 1941, surprise attacks on Pearl Harbor, the Philippines, Midway Island, Wake Island, and Guam. The Nazis are always remembered for the wholesale murder and mistreatment of concentration camp inmates, but they generally adhered to International Red Cross guidelines when dealing with their American and British POWs, but not those from the Soviet Union.

The discovery of the horrific mistreatment of American POWs by the Japanese was exposed and widely publicized after American forces liberated the Philippines and its POW camps, further fanning the flames of anti-Japanese hatred. The death rate for American POWs in Japanese-run POW camps was nine times that in those operated by the Nazis.

Some might argue that a test demonstration, in a remote area, of the atomic bomb’s destructiveness might have convinced the Japanese Empire to surrender. What if the demonstration had failed, then what?

Moreover, Tokyo’s enormous death toll and devastating destruction from the March bombings, the firebombing of multiple other Japanese cities, and the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on Aug. 6 did not immediately force Japan to surrender. It would take the atomic bombing of Nagasaki on Aug. 9 to force the Japanese Empire to finally surrender.

Some might argue that the bombs were not only aimed at the nearly defeated Japanese Empire but as a warning to America’s wartime ally, the Soviet Union, which loomed as a massive threat to American hegemony in a post-World War II world.

Regardless, Truman had no choice. Truman had one goal, saving thousands of American lives which would be certainly lost if the war had continued. It’s difficult to celebrate his choice as it resulted in so many deaths, but at least we can understand his reasoning.

May the world never again use these powerful weapons of mass destruction.

Newman is an amateur historian specializing in African-American history of the first half of the 20th century.