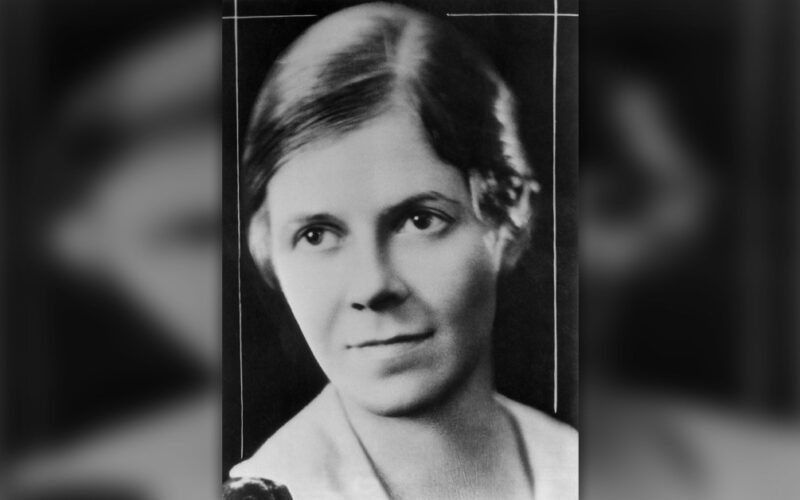

In 1936, Nancy Evans Titterton, 32, was a rising literary star. After years in the publishing business, one of her fiction works had been honored with the cover of Story Magazine, and she had a deal to write her first novel.

As an editor, the pretty, petite redhead from Ohio played an important role in the development of a popular Doubleday-Doran series, “The Crime Club,” which published many mystery classics over the years.

But after Good Friday, 1936, her name became associated with another form of crime writing — the screaming front-page tabloid headline.

“WOMAN AUTHOR SLAIN IN BEEKMAN PLACE HOME” was the Daily News take on Titterton’s April 10 murder.

“The talented wife of a National Broadcasting Company executive was bound, strangled, and flung into a bathtub yesterday by a powerful cat-like killer who invaded her boudoir at fashionable 22 Beekman Place,” wrote a News reporter.

Her husband, Lewis H. Titterton, 37, was the last to see her alive. He left their apartment around 9 a.m., heading to work. About two hours later, Nancy chatted by phone with a friend. Then she went silent.

Around 4:30 p.m., Theodore Kruger and John Fiorenza, the owner of an upholstery shop and his helper, arrived to deliver a love seat.

The apartment was quiet, but the door was open, so they stepped inside.

They found Titterton face down and naked in the bathtub, with a pink pajama top and another silk garment tied tightly around her neck. She had been bound, beaten, raped, and strangled.

Her husband was briefly on the suspects’ list but proved he was at work all day. Besides, the couple, who had been married for seven years, seemed totally devoted.

Tabloids hinted at steamy extramarital affairs— perhaps a gigolo, a former love, a famous author, but nothing came of those speculations.

House painters, the janitor, loiterers that residents described as degenerates, and one handsome dandy who was badgering a tenant all came under police scrutiny. But those leads yielded nothing.

Four days after the murder, police seemed stymied, with some declaring the “Bathtub Murder Case” a perfect crime that might never be solved.

There were few clues, a muddy footprint on a bedspread, a piece of horsehair, and 13-inch strand of cord found under the victim’s body.

Police believed it was a remnant of the cord used to bind her wrists. It would eventually lead directly to Titterton’s killer.

Bellevue biochemist Alexander Gettler, the brilliant toxicologist for New York City’s Office of Chief Medical Examiner, determined that the cord contained a stiff plant fiber called istle, used to make scrubbing brushes, burlap, and cords, wrote Harold Schechter in his book, “The Mad Sculptor.”

Police contacted rope makers in the region, asking if they used this fiber, which led to a Pennsylvania manufacturer who produced it. From there, New York City sleuths tracked the cord brand to a local wholesaler, who had records of selling a quantity of it to a Manhattan upholsterer the day before the murder.

The upholsterer was Theodore Kruger.

Detectives knew that Kruger’s helper had a troubled past. Fiorenza, 24, a dull grade-school dropout, had a criminal record dating back to when he was 12 and served two terms in prison. Alienists who examined him behind bars described him as a “psychopathic personality with a bad prognosis” and “potentially psychotic.” They also said he lived in a fantasy world and would take action without any thought about the consequences.

Twice, the system sent him out on parole.

“LOVED HER, SAYS SLAYER RE-ENACTING TUB MURDER,” was The News headline after his arrest, over the account of how Fiorenza “poured forth all the revolting details of his crime.”

Fiorenza visited the apartment the morning of the scheduled delivery to find out, he said, where she wanted to put the love seat.

As she showed him some of the places she was considering, he grabbed her from behind and pushed her down onto the bed. She started screaming and struggling, so he gagged her. “I had to tear almost all her clothing off,” he recalled.

Eventually, to silence her, he placed a noose he fashioned from her pajamas around her neck and squeezed. After the attack, he carried her limp form into the bathroom and dumped her in the tub, intending to finish the job by drowning her. That effort failed because he couldn’t find the plug.

Finally, with a knife from the kitchen, he cut the cords from around her wrists so he could take them along, leaving no clues. But he overlooked that one small piece of the cord.

At Fiorenza’s trial in May, his attorneys tried to raise doubt with stories of a “fiend who was on the loose in Beekman Place” who was badgering one of the Titterton’s neighbors. They also tried to show that their client belonged in an institution.

Experts for the prosecution, however, testified that the killer understood what he was doing and that it was wrong.

After more than 19 hours, the jury ultimately agreed that Fiorenza was sane at the time of the murder and deserved to be executed.

Months of appeals came to an end on Jan. 22, 1937, when Fiorenza took his place in the chair at 11:09 p.m. Three minutes later, he was pronounced dead.

He showed no emotion and offered no last words. But The News reported a strange comment he made to a guard as he waited.

“You don’t know all I’ve been through in this place. I don’t know why they don’t give me a chance.”