Theater review

FLOYD COLLINS

Two hours and 35 minutes, with one intermission. At the Vivian Beaumont Theater, 150 West 65th Street.

“Floyd Collins” is a story split in two.

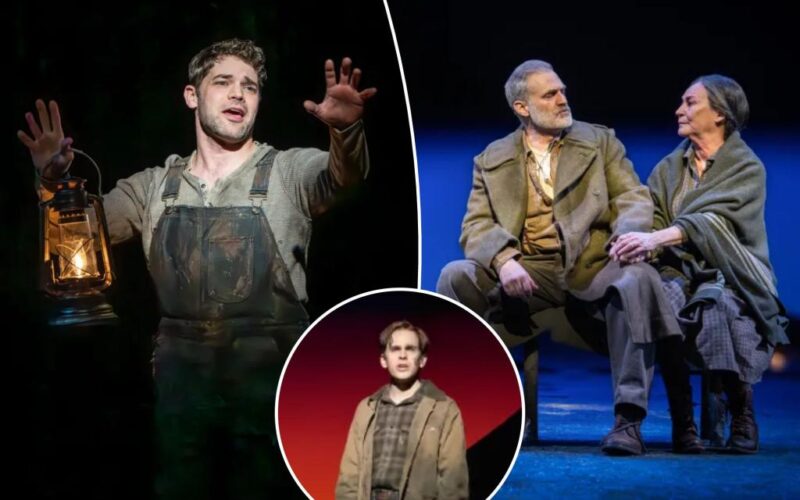

There’s the claustrophobic and cold Kentucky cave where the title spelunker, played by a golden-voiced Jeremy Jordan, becomes trapped after the rocks around him collapse.

Then, above that subterranean prison is his sunlit town, which, as Floyd’s harrowing 1925 true story turns into a frenzy of front-page news, plays host to a carnival of opportunistic human leeches.

That poor Floyd, like many a forward-thinking American explorer, got stuck “finding his fortune under the ground” while the predatory folks upstairs profited off the man’s suffering. It makes for a robust juxtaposition, and an always relevant one.

Yet “Floyd Collins,” receiving an ear-pleasing revival at Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont Theatre, is also a musical split in two — and not for the better.

Adam Guettel’s soaring 1996 score does to a dank, bat-dropping-filled cavern what composer Ennio Morricone did to 1960s frontier in films like “Once Upon a Time in the West” — packs it with unexpected romance and spellbinding allure.

As 37-year-old Floyd’s situation goes from “the stones are alive with the sound of music!” to dire and dark, his songs transition, too. Euphoric yodeling gives way to sanguine distractions and escapist fantasies. His prognosis is bleak, but Floyd knows he was doing what he loves most — caving.

Guettel’s sumptuous early work, although lyrically too “there’s gold in them, thar hills,” is enough of a reason to see the rarely performed show.

Harder for the audience to love is the other, rockier half: Writer-director Tina Landau’s hokey book that, like many history-based musicals of the 1990s — “Parade” and “Ragtime,” among them — flatly treats characters not as textured and relatable persons, but as mechanical stand-ins for weighty ideas.

That’s why “Floyd Collins,” audibly lush and visually beautiful, is never truly moving. We’re swept up by the music, and then given the brush by the script.

The slack-jawed 1920s Kentuckians and rude city intruders are so boiled down to their basic descriptions that the pot on the stove begins to smoke.

Nellie Collins (Lizzy McAlpine), just out of an asylum, desperately wants her brother to be free, and dad Lee (Marc Kudisch) is both traumatized and full of parental regret.

They don’t get much airtime to express themselves. And their big numbers, “Through the Mountain” and “Heart and Hand,” respectively, are both lacking in dramatic power.

In the case of Kudisch’s bench duet with Jessica Molaskey’s Miss Jane, that’s because putting on “Floyd Collins” at the Beaumont is not unlike reviving “Doubt” at Citi Field. Louder, Cherry!

But McAlpine, making her Broadway debut with a pleasant Sara Bareilles-like folk voice, is not quite up to the demands of this part yet.

The most engaging characters, puppy-dog Homer Collins (Jason Gotay) and scrappy reporter Skeets Miller (Taylor Trensch), exist in both worlds, squeezing through tight Sand Cave passages to visit Floyd while also witnessing the circus on the surface.

Trensch, who made an excellent Evan Hansen several years back, accesses his emotions with such honesty as morally confused Skeets wrestles with his exploding career and his personal duty to an imperiled new friend.

A reliably intriguing actor, he forms a palpable bond with Jordan’s Floyd, who at first enjoys learning of his newfound fame and then craves the company.

Jordan rebounds nicely after last season’s theme-park “The Great Gatsby.” Here, the tenor is actually great, excavating layers of a man we’re not told much about. (Who are we told much about?) In the best sense, this was the first time I’ve felt that he hung up his “Newsies” cap for good. Jordan, now more mature, could make a swell Billy Bigelow down the line.

Not all of Landau’s efforts deserve a finger-wagging. Save that for “Redwood.”

Her direction, especially considering the challenges of a largely bare and mammoth stage, is chockablock with striking images. Yes, it’s a drag that Jordan is glued to a chair on the far right for the bulk of the show. But individuals pinned down by heavy objects tend not to cross left, much as we’d like them to.

I only wish she had overhauled the dialogue, since Guettel’s music deserves better than guileless small-town caricatures.

And maybe one day it will be.

I’m not as positive a thinker as Floyd is, though, and if this is where the musical is at 29 years after its off-Broadway premiere, I imagine that, much like doomed Floyd, it ain’t budging.