In 1951, a blind 65-year-old man named Max Gerlach was listening to the radio when something jolted him to attention. A guest had come on who had just published a biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald — the late, great chronicler of the Roaring ‘20s and the pursuit of the American Dream.

Within minutes, Gerlach called the radio station. Not only did he know Fitzgerald, he said, but he inspired his masterpiece.

“I’m the real Jay Gatsby,” he declared.

At the time, no one paid Gerlach — a former car mechanic who had fallen on hard times — any mind. He spent the last years of his life trying in vain to communicate with Fitzgerald’s biographer, writing letters asking to let him tell his story. He ended up dying in New York City’s Bellevue Hospital in 1958, at the age of 73, forgotten.

That is, until about 40 years later, when another Fitzgerald biographer, Matthew Bruccoli at the University of South Carolina, found a note that a “Max Gerlach” had written in 1923 in one of the Fitzgerald’s scrapbooks. The last line was “How are you and the family, old sport?”

“It’s Gatsby’s defining phrase,” said Howard Comen, a private detective who Bruccoli enlisted to find out more information about the mysterious Gerlach in 2002. (Bruccoli has since passed away.) “That phrase, ‘old sport,’ is used 42 times in ‘The Great Gatsby.”

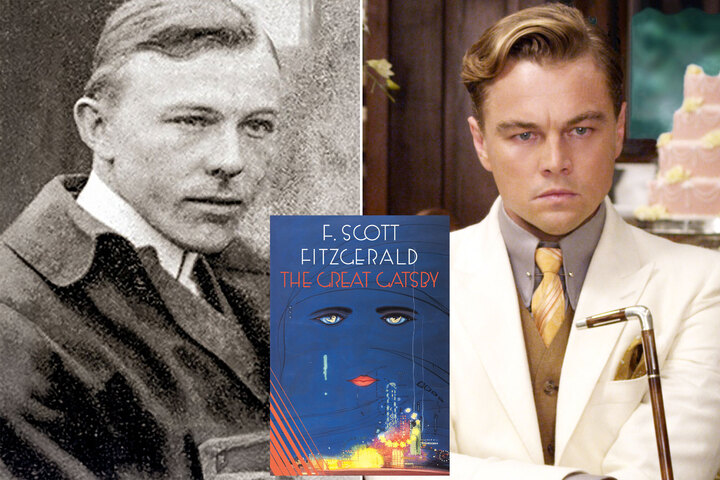

“The Great Gatsby” is celebrating its 100th anniversary this month. The novel’s elusive central character — a bootlegger with a mysterious past who throws lavish parties in the hopes of recapturing his lost love — continues to beguile.

Fitzgerald, who routinely mined his own life for his fictions, admitted that Jay Gatsby “started as one man I knew and then changed into myself.”

For decades, scholars, sleuths and fans have tried to figure out the identity of that “one man.”

“There seems to be an endless fascination with discovering who the real Jay Gatsby might have been, almost as if Fitzgerald were incapable of imagining such a man,” said James West, a retired English professor at Penn State University and the author of several books on Fitzgerald. He noted that there are multiple suspects.

Herbert Bayard Swope was a newspaper man who threw lavish parties at his mansion in Great Neck, that Fitzgerald and his wife, Zelda, attended.

Joseph G. Robin, a Russian-born immigrant to the U.S., changed his name, made a fortune in banking, and held fancy “automobile parties” on Long Island before going to prison for bribery and embezzlement.

Last year, journalist Mickey Rathbun published a book about her grandfather, George Gordon Moore, claiming he was “the real Gatsby.”

There are scores of people who believe they have some sort of connection to or insight into the person the great novel was based on.

“When I first took over as a general editor of Fitzgerald’s collected works, I got emails and letters from people who ‘absolutely knew’ who the original Jay Gatsby was,” West told The Post. “I answered all of them, but nothing ever came of it,” he recalled with a chuckle.

Yet among some Gatsby obsessives, Gerlach has emerged as a leading candidate. A 2014 book, “F. Scott Fitzgerald at Work,” by American-lit scholar Horst Kruse, argues that the German immigrant served as the basis for the character.

Last year investigative journalist Joe Nocera released an eight-part podcast series called “American Dreamer,” which delves into Gerlach and his supposed connection with this famous novel.

Gerlach was born in 1885 in Germany, though he later told everyone he was from Yonkers. His father — who served in the German Army — died when Gerlach was 2, and he came to the U.S. with his mother and her second husband when he was 9 years old. (For a while, Gerlach used his stepfather’s surname, Stork, before reverting back to his birth name.)

Gerlach studied auto engineering, and worked as a machinist, garage mechanic, car salesman and race-car promoter in New York, Chicago and Cuba. He actually was in Germany when World War I broke out in July of 1914, and he went to the American embassy to get out of Europe as quickly as possible. He applied to serve in the U.S. Army in 1918, toward the end of the war, likely to quell suspicions that he was a Hitler sympathizer.

It’s unclear when and how Gerlach met F. Scott and Zelda, but they definitely rubbed shoulders.

They might have connected via Gerlach’s work as an auto mechanic specializing in fancy, fast automobiles. The job put him in contact with New York City’s fashionable denizens. Cars play a major role in “The Great Gatsby” too, both as a plot driver and as a symbol of power, speed and destruction.

At some point, Gerlach began introducing himself as Max von Gerlach (which conferred some kind of noble standing) and circulated rumors that he was related to Kaiser Wilhelm II. He cultivated a posh accent, said he had gone to Oxford University and began calling everyone “old sport.” He also dabbled in some bootlegging, and consorted with gentleman crime boss Arnold Rothstein, who fixed the 1919 World Series, just like Gatsby’s boss Meyer Wolfsheim does in “The Great Gatsby.”

“He tried to remake himself,” Kruse told The Post. “He tells one story after another, in writing applications for the army, in interviews, in passport applications — he always evades the fact that he is a German immigrant. He invents stories about himself, all of these stories to make him an American, to be accepted, to be reinvented. And that is what Gatsby does.”

Of course, the tragedy of “The Great Gatsby” is that all the money in the world can’t elevate the poor “Gatz” into the upper-crust. The rich, materialistic Daisy — the love of his life — won’t leave her wealthy polo-playing husband for him. Gatsby will always be poor, always be “other,” no matter how many riches he acquires.

Fitzgerald published “The Great Gatsby” in 1925. It was a flop. In the summer of 1927, Gerlach was arrested for selling alcohol illegally, and lost a lot of money during The Great Depression. He tried to kill himself in 1939 by shooting himself in the head with a pistol, but blinded himself instead.

Fitzgerald died in 1940 at the age of 44, a drunk. Zelda perished in 1948 in a fire at the asylum where she was committed. Before she passed, she recalled to Henry Dan Piper — then a college student who would later write a book about Fitzgerald — that Scott had based Gatsby on a man named “von Gerlach,” who “was in trouble over bootlegging.”

“The Great Gatsby” was rediscovered during World War II, when it was released as a paperback. Around that time, Gerlach began telling people he was the model for the book’s protagonist. But a lot of Lost Generation men could see themselves in Fitzgerald’s doomed romantic hero, in his desperate pursuit of the American Dream.

“When I first started studying Fitzgerald, I thought it was easy — that there was a one to one relationship between a real person and a character, but the deeper you get into it, you find out it’s much more complicated,” West said. “Jay Gatsby in the novel is a fabrication. He contains characteristics from a number of different people … including Fitzgerald himself.”