Sumner Redstone moved closer to the stage, transfixed. A nude couple on a Harley-Davidson had just descended from the ceiling of Super Girls, a Bangkok sex club endorsed by Rolling Stone as “the very best in town.”

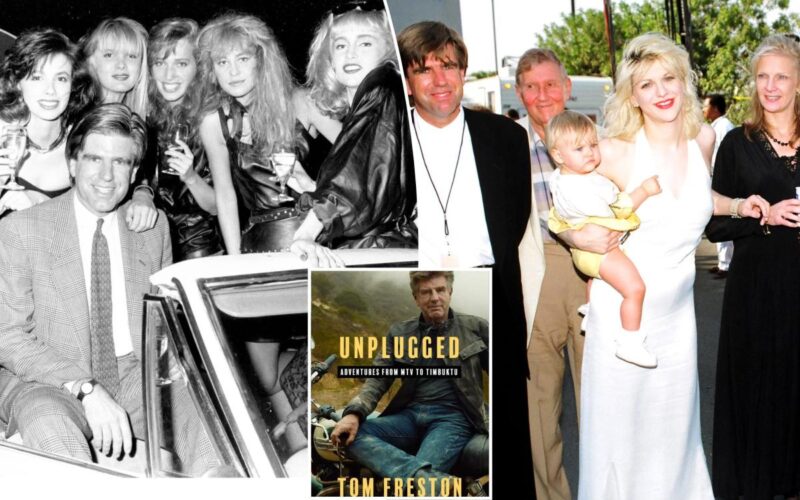

Redstone, then 72 and chairman of Viacom, stood “like a deer in the headlights, mouth slightly agape,” writes Tom Freston in his new memoir, “Unplugged: Adventures from MTV to Timbuktu” (Gallery Books, out now). The media mogul was rapt as he watched the couple have sex on the bike while the man gunned the throttle.

At the time, Freston was the MTV Networks CEO. Touring his boss around Thailand’s illicit offerings wasn’t in his official job description, but when Redstone announced plans for a 1995 Asia trip, he’d quietly asked: “Tell me what you know about the sex clubs in Bangkok. What about people f—ing? I want to watch people f–k. Can we see that?”

It’s just one of many wild stories in Freston’s captivating memoir, which chronicles his journey from smuggling contraband down the St. Lawrence River and escaping communist-coup Afghanistan to building MTV into a global phenomenon, complete with cocaine-dealing receptionists, “tequila girls” and sex on executives’ desks.

The 80-year-old media maverick — who gave the world “I Want My MTV” and launched Jon Stewart’s career — paints a portrait of American entrepreneurship at its most audacious and unhinged.

That night in Bangkok also included a program of women with unique talents when it came to opening bottles, writing letters and the like. Freston writes that when two front-row seats opened, Redstone grabbed his girlfriend Delsa and scrambled to get ringside. The trip opened the floodgates for the late business tycoon’s sexual appetites.

“Sumner went on to become the greatest high roller for commercial sex the world might have ever seen,” Freston writes. “In his later years, he spent over $150 million on a squad of comfort women. Two of the women made so much money off him that they opened their own charities.” Decades later, Redstone would brag to reporters “that all he craved was steak and sex three times a day.”

Long before vetting sex clubs for billionaires, Freston built MTV with its own brand of chaos.

“We had one receptionist who sold cocaine,” he writes. “Many of the staff found that convenient. People thought coke was the new No-Doz.”

One programmer nicknamed “Pig Virus” kept his stash in a desk drawer. “In a meeting, he’d nonchalantly open the drawer and take a hit off a collar stay, then politely look around. ‘Anyone need their beak packed?’”

People worked in flip-flops and bathing suits. There was just one rule: “No frontal nudity.”

In1988, someone flipped a lit cigarette into a garbage can at 2 a.m. and burned down an entire floor, which left 19 firefighters hospitalized. Local radio stations played Springsteen’s “I’m on Fire” and dedicated it to MTV. Lemmy from Motörhead would wander by with tequila.

Programming chief Les Garland ran what Freston calls “the Les Garland Show” from an office with Dom Pérignon bottles sent from record labels. “When female artists came calling, his staff would vacate, and according to office lore, the Gar Man would fornicate with a lucky few.” At one Christmas party, a staffer told Garland, “I just want you to know that I f—ed one of your assistants last night on your desk.” Garland clinked his glass and replied, “Congratulations, Bud.”

The revelry wasn’t limited to the office holiday party. At large festivities throughout the year, “‘Tequila girls’ in short shorts and cowboy hats, decked out in bandolier sashes packed with shot glasses, always circulated,” Freston writes. “A recruit to the Music & Talent department might last three years. To fire them, we might have to find a concierge to kick down a door in an LA hotel and revive them after a three-day cocaine binge.”

Freston grew up in Connecticut, the son of a WWII veteran, but discovered a hunger for action and adventure in his 20s. He left a marketing job to follow a girlfriend across the Sahara.

“As soon as we disembarked, I was hit with a high I would chase the rest of my life: the peculiar joy of disorientation,” he writes.

That led him around Asia, where he built Hindu Kush, importing clothing from Afghanistan and India. The business weathered “strikes, blackouts, malaria, dysentery, dust storms, cobras, riots, drug raids” but not politics. A 1978 Communist coup in Afghanistan upended his operations. Then President Carter’s administration, pressured by domestic manufacturers, restricted low-cost imports from India and he had to close up shop.

Needing a job, Freston joined Warner-AmEx in 1980, where 26-year-old “one-eyed hippie genius” Bob Pittman was developing an all-music channel.

“Were you smuggling hashish?” Pittman asked of his past work experience. “Not really,” Freston replied. “’Not really?’ Pittman said. ‘That means you were! You’re hired!’”

MTV launched in August 1981 with just 2.1 million households. It was mostly only available to cable subscribers in New Jersey.

“The cable operators thought no one’s going to watch music videos,” he told The Post in an exclusive interview. “But the actual music fans ate it up.”

By 1983, Freston was recruiting stars for the “I Want My MTV” campaign. In Switzerland, David Bowie invited him to a sauna. When Freston arrived, there was one other person in the fog: Paul McCartney. “Here I am with a towel wrapped around me with two of my ultimate heroes,” Freston told The Post. “They want to know, ‘What’s MTV all about?’ We’re throwing water on the rocks. It was very surreal.”

When criticism mounted that MTV wasn’t playing black artists, Freston acknowledged the problem. The breakthrough came in 1983 with Michael Jackson. “‘Billie Jean’ was a smash from day one,” he writes. “We wanted that video for our channel.” For the “Thriller” video, they ran magazine ads with start times and “our ratings were huge,” Freston told the Post.

When ratings softened in 1985, Freston led a team who “called ourselves ‘the MoFos,’ short for ‘motherf—ers,’” advocating expansion beyond music videos. That experimentation shaped Comedy Central. When Jon Stewart took over “The Daily Show” in 1999, he told Freston: “You guys remind me of one of the great New York Yankees teams… more like a family than a business. Were it not for you all, I’d be bashing Viacom like a piñata.”

In 2001, Freston traveled to Havana with producer Brad Grey and Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter. The met with Fidel Castro who asked in English, “Who of you makes ‘The Sopranos’?”

Grey sheepishly raised his hand. The dictator — who’d overthrown gangsters and survived CIA assassination attempts — patted his shoulder: “That’s my favorite show.”

Freston’s relationship with Redstone could be volatile. He writes of how during one meeting about Tom Cruise’s contract — shortly after the star’s infamous couch-jumping moment on “Oprah” in 2005 — Redstone exploded: “Tom Cruise is a F–K. He cost Mission: Impossible a hundred million dollars. Women EVERYWHERE hate him. I HATE him.”

Five years later, Redstone abruptly fired Freston during a Labor Day weekend meeting at his Beverly Hills mansion, ending his more than two decades building MTV from scrappy cable experiment into a corporate powerhouse. His dismissal led to a revolt, with an estimated 1,000 employees rallying in his honor.

“I wanted to just slink out, sort of ashamed and defeated,” Freston told the Post. “But there’s everyone I worked with, all chanting my name like I’d won the Super Bowl. I started to well up. It was really emotional.”

Jobless, Freston reconnected with Saad Mohseni, an old friend in Afghanistan who had launched Moby Media. Mohseni’s Arman FM station burst onto the air in 2003, playing Shakira and Michael Jackson after the Taliban had allowed only prayer chants. Preston helped build it into an empire. “Afghan Star,” a knock-off of “American Idol,” became such a hit that the government wouldn’t turn off electricity until it ended.

Freston also worked as a consultant helping Oprah Winfrey launch OWN: the Oprah Winfrey Network in partnership with Discovery Communication. He found consulting frustrating.

“If you don’t have official responsibility for anything, you don’t have the authority to tell people what to do,” he writes.

Currently, he serves as board chair of Bono’s One Campaign fighting poverty in Africa and has no plan to fully retire anytime soon.

“There’s this friend who just turned 100 and said to me, ‘The future is bright,’” Freston said with a laugh. “I keep thinking I’ll cut back. But I can’t imagine retiring and doing nothing.”

He’s troubled by the younger generations’ anxiety and has some wisdom for them.

“Lighten up. Don’t stay in a job that you don’t like. Don’t be afraid to get off the treadmill,” he advised. “You can improvise a life.”