Public transit is New York’s superpower. Every day, against all the odds, it holds the city together and makes it go, connecting millions of riders to jobs, families, healthcare, and community. New York wouldn’t be the same without it.

But public transit is under extreme duress, plagued by delays, outages and disruptions tied to decades-old backlogs in upkeep and improvement, with consequences for all New Yorkers. In a city where physical mobility and economic security and vitality go hand in hand, public transit needs championing. It needs support and funding worthy of its central role in the city’s life and long-term health.

As Albany leaders put together a state budget in the coming days, they’ll need at least $2.2 billion in new, recurring funds for the MTA’s next capital plan, the five-year outlay that pays for system maintenance, upgrades and expansion.

The launch in January of congestion pricing was a breakthrough: a new, dedicated source of annual revenue for revamped and expanded transit service. But even if tolls for motorists in Manhattan yield every dollar of the more than $500 million projected annually, it’s only a first step — and its funds are already allocated for the previous capital plan.

Securing the future of public transit in New York will require more.

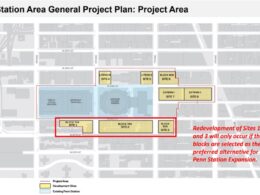

A lot is riding on the next capital plan, whose proposed price tag is $68 billion (with $47 billion going to New York City Transit). Letting critical repair work and new projects lag for another generation, or another five years, is an invitation to chaos.

Thankfully, there is no shortage of promising ways to help pull mass transit back from the brink and cover what congestion pricing alone won’t.

New York’s ultra-wealthy are a place to start. Invest in Our New York, a statewide coalition of organizations advocating for the working class, has proposed a package of legislation that would raise taxes on incomes above $450,000, capital gains, corporations, heirs and the state’s 130 billionaires.

IONY’s proposals aren’t transit-specific, but directing a portion of those new tax revenues towards an engine of that wealth — New York’s mass transit system — would be an investment in our future. Further, when the MTA’s own Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee (PCAC) studied a range of potential transit funding sources, it concluded that taxing high incomes and second homes could have raised $13 billion of what was an estimated $43 billion for unmet transit system needs.

The argument behind congestion pricing points to another way forward: Driving imposes costs on the city that it needs to recoup for the benefit of all New Yorkers. PCAC’s analysis found that adding a Vehicle-miles Traveled (VMT) fee to the state’s existing gas and highway use tax would have raised $10.4 billion over five years. Smaller-scale hikes in the city’s gas tax, motor vehicle registration fees and petroleum business tax could raise an additional $3.4 billion, PCAC reported.

In 2018, a year before Albany voted to implement congestion pricing, the late UCLA urban planning legend Donald Shoup (who just died last month) wrote that the city could raise $3 billion per year from charging for street parking. There’s also a proposal to flip the formula for distributing gas tax revenue collected in the greater New York City area so that most of it will go to public transit instead of roads. The point is not to punish motorists, but to require them to contribute more to the city’s improvement, and give them a great alternative: functioning public transit.

Transit riders are stakeholders, too; by paying fares they contribute almost a quarter of the daily operating budget that keeps New York moving. Tolls, taxes and federal contributions make up the rest. We don’t simply pay for transit at the turnstile though. We pay with our time, in unpredictable amounts, and, too often, with our fear, frustration and aggravation.

But for all the headaches the system causes, public transit is a small, beloved oasis of affordability in a city beset by rising costs. It’s a wonder of mobility, but one that’s increasingly vulnerable to climate change, and scarily reliant on daily acts of commute-saving magic performed by repair crews, operators and supervisors.

Our superpower is endangered. It needs rescuing. And state leaders can act from a place of genuine abundance by investing fully in mass transit. New York can’t afford anything less.

Valdez is a freshman member of the Assembly from the 37th District in Queens, which includes Long Island City, Sunnyside, Woodside, Maspeth, and Ridgewood.