A long-time Queens resident, Chris Ortiz went to a nearby gym last summer expecting nothing more dramatic than his usual workout.

But within minutes that day, his heart stopped, then started again after a defibrillator shock — turning an ordinary Sunday into the kind of save that emergency doctors call rare — and defying otherwise long odds of survival.

“It was four days before my 60th birthday,” Ortiz, a respiratory therapist at New York University who migrated to the United States when he was 9-years-old, told the Daily News, adding the morning it happed, nothing felt like a warning.

Ortiz said he and his wife had come home from their granddaughter’s 16th birthday party the night before and decided to go to the gym the next morning around 9 a.m. At the gym, they split up, with his wife headed downstairs for a treadmill and Ortiz staying upstairs for weight training.

Not long after, his wife got a call, “and she was very surprised,” Ortiz said.

“She was like ‘is this a joke?’ She thought it was somebody kidding with her, because she was told that I just had a heart attack. I am in the hospital,” he recounted — noting he doesn’t remember collapsing, or the ride to the hospital that followed.

Ortiz was lucky to have a Mount Sinai Queens nurse on the gym floor that day who quickly made sense of the situation and realized he was having a heart attack. The nurse not only performed CPR on him but also alerted the hospital to keep the operation theatre ready for Ortiz. After a 911 call, an ambulance quickly arrived, he said.

Heart disease remains the nation’s leading cause of death and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says cardiovascular disease kills someone about every 34 seconds in the U.S.

Dr. David Power, an interventional cardiologist at Mount Sinai Queens, told The News that Ortiz was brought to the hospital within the crucial minutes after a heart attack that determine the fate of a patient. A defibrillator shock had already restarted his heart, before he arrived at the emergency room.

Minutes mattered because the cause was severe, Power explained, adding Oritz was taken straight to the catheterization lab.

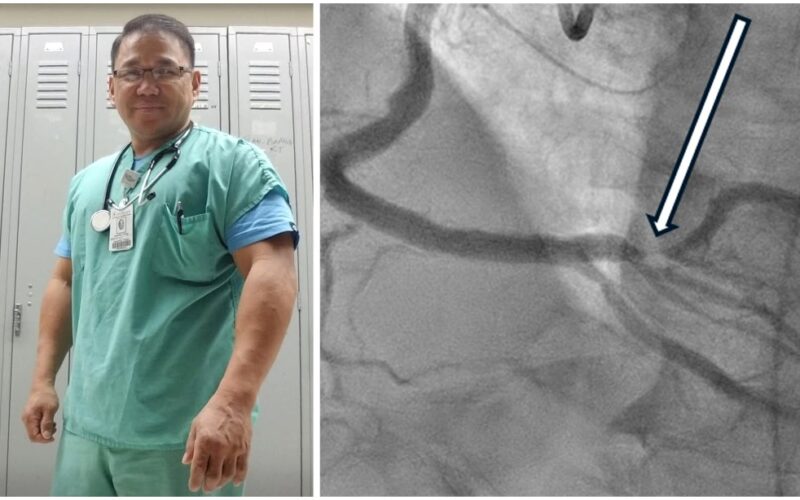

“He was found to have 100% blocked artery, which we opened up with a balloon, and then we placed a stent to restore blood flow to the heart,” Power said.

A before and after image of Chris Ortiz's blocked artery. (Courtesy Mount Sinai Heart System)

It is easy to hear “blocked artery” and imagine something slow. But cardiac arrest is not slow.

Nationally, roughly 350,000 people experience out-of-hospital cardiac arrest each year, with about 90% dying, according to American Heart Association figures. The difference between life and death often comes down to whether someone nearby starts CPR and uses an Automated External Defibrillator (AED) fast enough. Ortiz was lucky to have both immediately.

“In cardiac arrest, every minute counts,” Power said. “We were able to open up the artery in less than 90 minutes, which is the kind of goal we aim for.”

For Ortiz, the setting shaped the outcome. Collapsing at a busy gym meant he was noticed right away, that CPR and an AED were used within minutes, and that he reached the hospital fast.

“It could have happened when I was home by myself and I could have passed out. Then, it would have been a whole different story,” Ortiz said. “But the fact that it happened in a public place and they recognized right away what to do… I got help immediately.”

Chris Ortiz and his wife. (Courtesy Chris Ortiz)

Despite staying active, Ortiz had risk factors that didn’t get much attention as he maintained an “I’m fine” mindset. He struggled with diet and had high cholesterol, trying to manage it on his own and repeatedly declining medication, he said. But the American Heart Association warns such an attitude can turn preventable risks into emergencies.

Many of the risks that feed into such an attitude are silent until they are not. Power said the best way to prevent cardiac emergencies is to identify and manage modifiable risks — such as high blood pressure and cholesterol, diabetes, smoking, excess weight, and inactivity — while recognizing that age, genetics, and family history can’t be changed.

Family played an important part in Ortiz’s story — both his fear and motivation. He talks about children and grandchildren as the people who would have lived with the consequences if he had survived with severe damage. “I could have ended up basically a vegetable in a nursing home right now,” he said.

He also carries a private sense of irony. Two of his daughters have been involved in saving strangers in emergencies, which, to him, makes his own rescue feel like a strange echo. “Maybe it’s because my children saved someone’s lives that God sent the ER nurse in the gym that day to save mine,” he said.

Chris Ortiz at a Mets game (left) and with his grandson after his heart procedure last year (right). (Courtesy Chris Ortiz)

Ortiz says he bounced back quickly and was discharged from the hospital soon after the heart procedure. But changing long-standing eating habits has been the most difficult part of his recovery as he tries to prevent another emergency, he said.

“Don’t wait until you start having the symptoms and have the cardiac arrest like I did,” he warns. “Prevention is the best thing.”

He said he also wants people to understand who else pays when someone refuses to change. “If you decide not to take care of yourself, the ones who suffer is your immediate family,” Ortiz warned.

Since July last year, Ortiz says what’s changed most for him is his sense of time — it doesn’t feel endless anymore, it feels counted, he said.

“I’m trying to not work as much and spend more time with my family and not take things so seriously all the time,” he said. “Time is not given. All go away from me any moment… this is all extra for me.”