Surely, he had to be joking.

That was the first thought that went through the minds of officers at San Francisco’s Hall of Justice when Albert Walter Jr., 28, strolled in on June 17, 1936. The well-dressed stranger was too calm — nonchalant was how police described him — to be talking about murder.

“My conscience hurts me,” he said. “I strangled a girl.”

Officers didn’t believe him until Walter led them to the apartment of Blanche Cousin, a pretty bookkeeper from Idaho. What they found there was no laughing matter.

Cousin’s body was sprawled on the bed — nude with a silk stocking tied tightly around her neck.

“SLEW GIRL FOR REVENGE ON SEX, SAYS STRANGLER,” was the Daily News headline explaining his motive on June 19, 1936.

“When I was 14, an older woman took advantage of me. She gave me a terrible disease,” Walter said. “I dedicated my life to vengeance against women — all women.”

New York Daily News

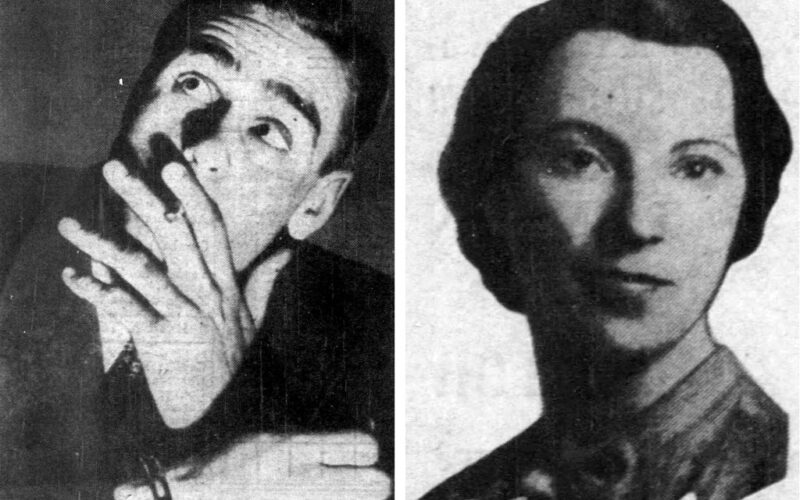

Albert Walter, Jr. (New York Daily News)

He boasted of having “seduced, corrupted, and ruined as many of them as I possibly could. This thing — this killing — is no surprise to me. I knew, deep in my brain, that eventually I would achieve the supreme vengeance — that I would kill a woman.”

Such a confession was almost a guaranteed trip to the gallows at San Quentin, which was just fine by Walter.

“That’s just what I want. It’s my way of committing suicide,” he told his captors. “I confessed because I want to die. I’m going to let the state do it for me.”

Cousin met her killer when they were both passengers on a bus bound for San Francisco from Salt Lake City. They started to see each other when they reached their destination.

On June 16, Cousin invited Walter for supper at her home. After their meal, they settled onto the couch, Walter recalled.

“She led me on, teased me. Then, when I was filled with passion, she repulsed me. I just couldn’t stand it,” he said. “So I gripped her throat in my hands and pretty soon she didn’t struggle any more. She made no outcry.”

He stripped off her slacks and sweater and carried the inert form to the bed.

“I ravished her. By ravishing, I mean what the word says and means. I don’t know whether she was still alive when I violated her,” he said. “To make sure she was dead, I knotted a stocking around her neck.”

The “Silk Stocking Killer” is how the press would frequently refer to him from then on.

Cousin, 31, was a quiet, serious redhead who grew up on her family’s Idaho ranch. She planned to attend business college in San Francisco and pursue a new job.

“She has performed her duties faithfully and well. Her work and conduct were first class and her capabilities good,” wrote a supervisor at her last job at the Latter Day Saints Hospital in Idaho Falls. Police found the letter of recommendation in her apartment.

There were no such glowing assessments in Walter’s background.

The San Francisco Examiner described him as a “man of many occupations but now unemployed.” Born in Boston, Walter had spent years bouncing around the country and into different jobs — salesman, chef, butler, lumberjack, law clerk, and restaurant manager. A short stint in the Army ended with his desertion and a year at Alcatraz.

Following his release, the wanderings continued even after he married a tall, blond restaurant executive in New York City.

News reporter Julia McCarthy tracked down his wife — Angela Hoskins Walter — in her apartment on Jane St. Angela spoke of his frequent disappearances over the year since the wedding, starting four months into the marriage.

“I was greatly upset and I went to some of his friends and told them about it,” she recalled. “They said they were not surprised as he always had been peculiar.”

Her spouse later explained that he ran away because he feared he would harm her.

New York Daily News

Angela Hoskins Walter told a Daily News reporter about her husband’s frequent disappearances. (New York Daily News)

Walter refused to plead not guilty by reason of insanity. He wanted to hang but California officials and relatives refused to let it go at that.

The state appointed a three-member panel of alienists to probe his mind and perhaps save him.

His father, Albert Walter, Sr., a real estate salesman, offered his own proof of insanity. He blamed bad genes, saying the boy’s mother was “erratic, nomadic and abandoned him when 3 years old.”

Madness ran in the family, including an aunt, grandmother, and grandfather. Walter Sr. also told of his son’s early criminal activities, which started in grade school, and deviant sexual drives.

Walter Jr. insisted it was his right to choose the noose. “I am determined to stick to my plea of guilty,” he told reporters from his jail cell. “I want to be hanged and get it over with.”

After three hours talking to Walter in his cell, the alienists determined he had an “abnormal state of mind but it is not insanity.”

It took just 23 minutes for a jury of eight men and four women to agree with the experts and grant Walter his death wish.

“Good,” was all the doomed man said when he learned of the sentence.

Walter maintained an eerie calm in the hours leading up to his hanging on Dec. 4, 1936. The deputy warden told reporters he slept most of the night, asked for a breakfast of hotcakes, bacon, and one egg.

The Silk Stocking Killer left no message behind and uttered no last words on the gallows. But shortly before he began his final walk, he said to the prison chaplain, “I’m ready to go, and so help me, Father, I’m eager to go.”