In New York’s mayoral election, plenty of candidates claim to be the anti-Trump. But, when it comes to protecting workers’ rights and reducing economic inequality, the better question is who will be the neo-LaGuardia. The “Little Flower” served as the city’s mayor from 1934 to 1945. A Republican, Fiorello LaGuardia was an aggressive advocate for egalitarian and anti-corruption New Deal policies, particularly in support of working New Yorkers at a time when the ambitions of the federal government remained limited.

An example: In 1934, newly elected Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia watched a citywide hotel strike drag on for a second month, and determined to find an amicable settlement for the workers. The industry, represented by the Hotel Association, sparked the strike by firing union activists who refused to join a company union.

The federal government’s untested mediators saw their job as getting the strikers back to work; nothing more, nothing less. The hotel bosses doubted the feds even had that authority, and steadfastly refused to negotiate with their workers’ chosen representatives.

1934

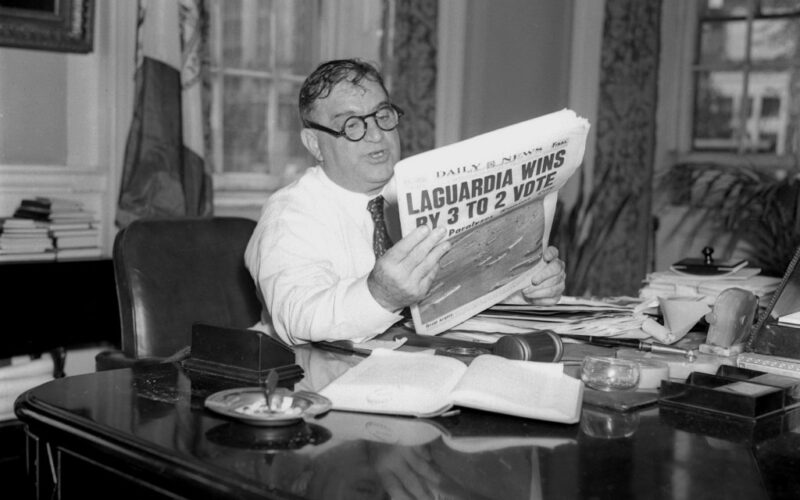

Stanley Brown/New York Daily News Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia giving a radio address about his first 100 days in office.

Without labor peace, more Depression-plagued hotels would slide into bankruptcy, but hotel owners refused LaGuardia’s offer of conciliation. “If they cannot understand the spirit of cooperation in which the mayor approaches them to settle this very vexing disturbance,” LaGuardia said when the hotel managers rebuffed him, “then they must assume full responsibility.”

The mayor responded by siccing the city’s health inspectors on the picketed hotels, producing 600 summonses in 48 hours, embarrassing the bosses and humiliating the scabs (who were forced to line up and drop their pants for mandatory hernia exams). The strike ended the following week.

Four years later, the Hotel Association signed a neutrality card check agreement on behalf of the city’s hotels with the Hotel Trades Council — a new umbrella organization representing every union that spoke for the city’s hotel workers. The organization remains a 40,000-member strong powerhouse for hospitality workers to this day.

Although the landmark 1935 National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) made it the policy of the federal government to protect and promote collective bargaining, the law initially excluded many local businesses (like hotels, restaurants, car washes and industrial laundries) that didn’t cross state lines. LaGuardia pressed the state Legislature to pass a “baby Wagner” law for local businesses, and he used his bully pulpit to fight for a “100% union city,” leveraging everything from tax breaks to tourism support and even the city’s water supply to pressure employers to recognize unions for their workers.

As New Yorkers ready for our local elections, the Trump administration is trying to return labor relations to the “law of the jungle” that characterized the decades before the NLRA. Thanks to legal challenges by billionaires Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, Texas’ conservative federal appeals court is poised to send cases to the Supreme Court with the aim of declaring the NLRA unconstitutional.

Their legal argument, based on last term’s Securities and Exchange Commission vs. Jarkesy, is that members of the rule-making National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) are too hard for a president to fire and, thus, are improperly appointed. Their political logic is that the Supreme Court’s 6-to-3 conservative majority gives them enough votes to overturn the main federal labor law and strip most workers of the right to organize. Such a case could be heard and decided as soon as next year.

Meanwhile, Trump has asserted that he can fire NLRB members, like Biden appointee Gwynne Wilcox, anytime he wants (because, of course he has). Although a lower level court has temporarily reversed Wilcox’s illegal termination, in the near future Trump may simply allow NLRB seats to remain vacant as terms expire, denying the labor board a quorum to issue any decisions. Before then, shadow president Elon Musk will try to illegally fire most of its staff, rendering the NLRB incapable of conducting union representation elections or investigating discrimination against union activists.

As this threatens to leave most workers with few if any federal legal protections that corporations are bound to respect, we should aspire for a mayor who will be like LaGuardia and use the bully pulpit and powers of the office to crusade on behalf of non-union workers and a beleaguered labor movement for a fully unionized Big Apple.

This is harder than it sounds. First of all, those who oppose workers’ rights (but won’t admit it), will criticize a mayor who “takes sides.” The New York Times, for example, accused LaGuardia of supporting the hotel strikers in “a most offensive and even malicious way.” But employer union-busting is even more offensive and malicious. According to researchers at Cornell University, employers threaten to cut benefits or shut down locations in half of all union elections, and fire activists in one of three cases.

Despite conditions that resemble a dictator’s reelection, unions have been winning a larger percentage of union certification elections — 79% in 2024 — as workers increasingly see the need for protections from corporate greed and callousness. And that’s while there’s ostensibly still a federal labor board to police these matters.

This renewed energy from the labor movement, and public support for labor unions, is precisely why Trump and the billionaires are targeting the legal rights of workers. But even under the pro-union Biden administration, less than half of all successful union certifications resulted in a collective bargaining agreement. To raise wages and win enforceable safety and job security, workers need more than a neutral arbiter in a lengthy legal process. They need a true champion of labor unions, willing to leverage his or her moral authority and political power to hold the bosses accountable.

The 1934 hotel strike that was championed by LaGuardia was technically a failure, with the workers’ loyalties spread out across three unions — one Communist; one, an alliance of the democratic Left; and one mobbed up by the Dutch Schultz gang — and the law stacked against them, while employers were willing to go broke to maintain “control.”

As I explain in “We Always Had a Union: New York’s Hotel Workers Union, 1912-1953,” hospitality workers organized for decades — with a wide variety of tactics, including boycotts and sabotage — before they finally enjoyed the protections of a union contract. More than 10,000 hotel workers remained dues-paying union members during a hostile 1920s that saw most unions in decline.

Their unions rocked the city with four industry-wide strikes between 1912 and 1934, before settling the Industry Wide Agreement that encouraged peaceful resolution of disputes. (LaGuardia’s enmity towards the Hotel Association went back to 1918, when the bosses rejected his offer, as a congressman and returning war hero, to mediate an earlier citywide strike. Major LaGuardia denounced them as “hostile to the principle of collective bargaining.”)

Thanks to that long struggle, the Hotel Trades Council’s contract today provides a minimum wage for housekeepers of about $40 an hour, with generous pension and health care benefits — affording hotel workers a middle-class lifestyle that all workers deserve, but many are denied due to our broken labor laws.

The removal of federal protections for union organizing may ultimately create opportunities for states and cities like New York to pioneer new local labor laws, like those in LaGuardia’s time. But the unmatched power of billionaires and multinational corporations requires leaders who will resist bribes, threats and propaganda; who will array City Hall’s vast powers — everything from taxation and zoning laws to health, buildings and consumer affairs investigators — against union-busting bosses in defense of workers who try to form unions and win contracts.

“I am criticized by cheap politicians because they say I favor labor,” LaGuardia once told an audience. “I do.” Let us find a mayor who will say “I do, too.”

Richman teaches labor history at SUNY Empire State University. His book, “We Always Had a Union: The New York Hotel Workers’ Union, 1912-1953,” will be published on April 8.