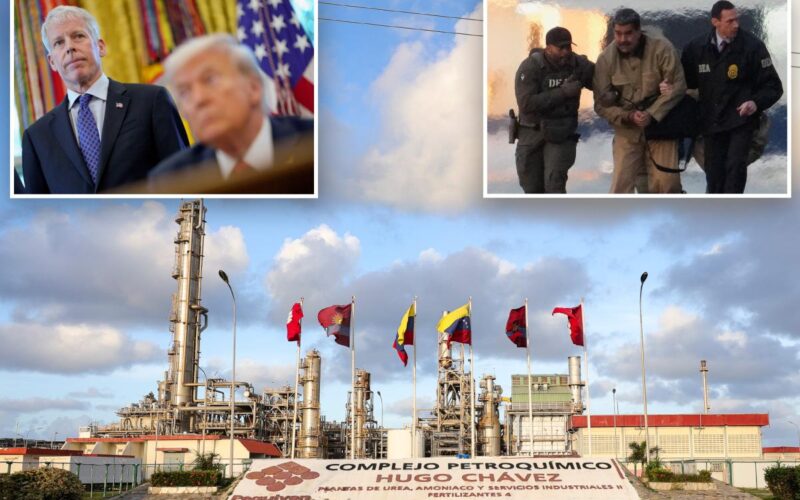

The Trump administration said Wednesday it will control Venezuela’s oil sales “indefinitely” in the wake of deposed strongman ruler Nicolás Maduro’s capture.

Energy Secretary Chris Wright asserted the US will market and sell Venezuelan crude, with proceeds held in US-controlled accounts that he said “can flow back” to Venezuela, a day after President Trump said Venezuela would turn tens of millions of barrels of oil over to the US.

“Instead of the oil being blockaded, as it is right now, we’re gonna let the oil flow … to United States refineries and around the world to bring better oil supplies, but have those sales done by the US government,” Wright said at Goldman Sachs’ Energy, CleanTech & Utilities Conference in Aventura, Fla., on Wednesday.

The US will first move to sell millions of barrels of Venezuelan crude currently stuck in storage because of US sanctions and a blockade, and then take over the sale of ongoing production for the foreseeable future, according to the energy secretary.

“We’re going to market the crude coming out of Venezuela, first this backed-up stored oil, and then indefinitely, going forward, we will sell the production that comes out of Venezuela into the marketplace,” Wright said.

On Tuesday, Trump publicly laid out his own vision for Venezuela’s oil sector following the arrest of Maduro, saying the upheaval created an opening for the US to step in and restart production.

The commander-in-chief detailed the plan on Truth Social, saying Venezuela’s interim authorities would hand over between 30 million and 50 million barrels of sanctioned oil to the US and that he had directed Wright to execute the sale.

Trump said the crude would be shipped to the US, sold at market prices and placed under American control to be used for what he described as the benefit of both countries.

He told NBC News that American oil companies could get Venezuela’s oil fields “up and running” in less than 18 months, after years of decay and neglect.

The president said the rebuild would require billions in private investment, with Washington potentially footing the bill later.

“A tremendous amount of money will have to be spent, and the oil companies will spend it, and then they’ll get reimbursed by us or through revenue,” Trump said, predicting the companies will “do very well” under the arrangement.

Trump has framed control of Venezuela’s oil as part of a broader political reset following Maduro’s arrest, saying the US wants to restart production, stabilize the country and ultimately hold elections.

Wright said Wednesday that Washington plans to send supplies and equipment to Venezuela for a larger-scale revitalization and to create conditions for major American oil companies to return.

Oil executives were aware the administration was exploring options in Venezuela, but they were not consulted ahead of the US operation that led to Maduro’s capture last week, according to Trump.

Asked whether he had spoken with leaders of Exxon Mobil, Chevron or ConocoPhillips, Trump replied Monday it was “too soon” to say, adding: “I speak to everybody.”

The president is expected to meet Friday at the White House with executives from Chevron, Exxon Mobil and ConocoPhillips to discuss potential investments, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Trump has also warned Venezuela’s interim President Delcy Rodríguez to cooperate with the US plan or face what he described as severe consequences.

Venezuela is a challenging environment for oil companies to re-enter, experts say. Years of neglect have left oil fields, refineries and pipelines in severe disrepair.

Industry executives and analysts have warned that restoring meaningful production would require tens of billions of dollars in upfront investment, along with years of sustained work in a country still facing political instability and legal uncertainty.

Even with Washington’s backing, oil executives have privately questioned whether the economics make sense, particularly when companies have other global projects offering quicker, less risky returns.

Several analysts have cautioned that persuading shareholders to commit massive capital to Venezuela would be a hard sell, given the country’s history of expropriations and the long timeline required to see profits.