After several election cycles where polls were off base and media coverage was biased, prediction markets promised to be technology’s answer to flawed polling, offering real-time data and financial incentives.

But that new technology has also made it easier for major players to manipulate public perception, raising concerns about what amplifying that information could mean.

“Markets are open to manipulation by a small number of deep-pocketed market participants.” Dr. Don Moore, the Lorraine Tyson Mitchell Chair in Leadership and Communication at University of California, Berkeley, told me.

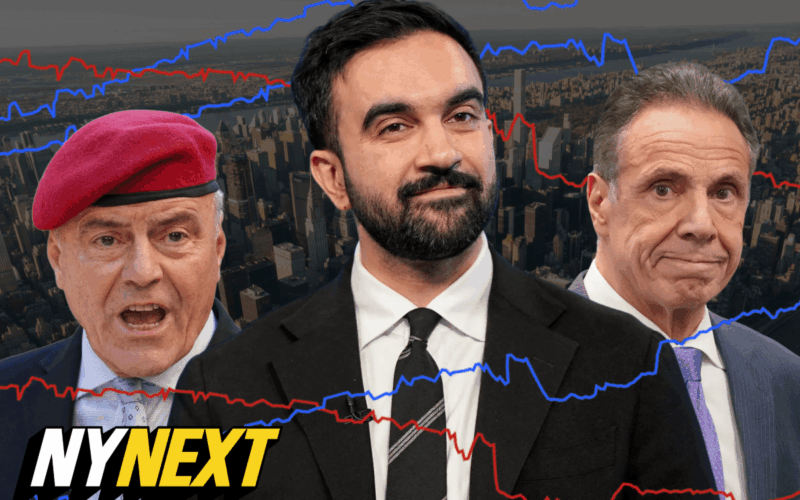

I’ve been surprised over the last few weeks and months that despite polls (at times) showing Cuomo inching ahead, the betting odds on platforms like Polymarket and Kalshi have stubbornly shown Mamdani leading with more than 90% of the vote. No headlines (and photos with terror sympathizers), candidates dropping out and making endorsements (looking at you, Eric Adams), or poll has changed that.

On Polymarket — which isn’t technically able to operate in the US, though that’s about to change and many get around it with VPNs — betting appears to be dominated by a single whale.

This story is part of NYNext, an indispensable insider insight into the innovations, moonshots and political chess moves that matter most to NYC’s power players (and those who aspire to be).

While users don’t have to disclose their real names, the platform’s blockchain-based system makes all trading activity public — positions, betting amounts, trading history and account creation dates are all visible. One account, dubdubdub2, that joined last month has spent over a million betting on a Mamdani victory, according to a review of the website. The user has also continued to snatch up shares over the last week. I’ve reached out to Polymarket for comment.

“Betting markets present an opportunity to manipulate perception,” Moore, who specializes in decision making and politics, said. “One fear is if your candidate is way ahead in early results you don’t need to get to the poll, but there is a countervailing motivation that some benefits accrue to candidates who seem to be pulling ahead.”

At press time, the polls showed Mamdani at 43.2% and Cuomo at 28.9% (though that narrowed to a possible win for Cuomo considering the margin of error if Sliwa drops out), while Kalshi and Polymarket had Mamdani’s odds of victory at 92% and 93% respectively.

The high odds of a Mamdani victory have been on full display with New Yorkers seeing ads for Kalshi, Polymarket and the like amplified across main thoroughfares like Times Square and Penn Station. What does it mean for conceivably hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers to get blasted on their commute with the odds of a Mamdani mayoralty at north of 90%? And could the sheer volume of foot traffic in front of those signs potentially shape how people are prioritizing voting and who they vote for?

Betting markets operate without the same ethical guardrails as pollsters, who typically embargo their data until after polls close on election night to avoid influencing voter behavior.

A spokesperson for Kalshi, which is approved to operate in the US and regulated by the CFTC, noted that the platform has big market makers that act as safeguards by taking the other side of the trade and aiming to prevent manipulation. During the 2024 presidential election, the spokesperson said, a single bettor spent $85 million buying up Trump shares, pushing his odds to 70% on Polymarket while Kalshi’s institutional counter-pressure kept them below 65%.

While those in the Cuomo camp acknowledge that traditional polling has flaws (after all it sure didn’t get the numbers in the primary right), they are also concerned about what the betting markets mean. A source close to the campaign told me, “I get texts every day from people who don’t know what it is … and I don’t think it paints the right picture for folks.”

This isn’t the first time betting markets have raised concerns. In 2012, the prediction market InTrade showed Mitt Romney’s odds surging on election night, prompting concerns within the Obama campaign about whether the numbers were reflecting reality or attempting to shape it.

But now that they’re bigger and more visible than ever, they at the very least require a bit of scrutiny, given the numbers flashing across Times Square aren’t just predictions — they could be potentially persuasive tools.