For decades, many have blamed Yoko Ono for breaking up the Beatles. But, according to a new book, Ono may have actually prolonged the life of the seminal rock band — and of John Lennon himself.

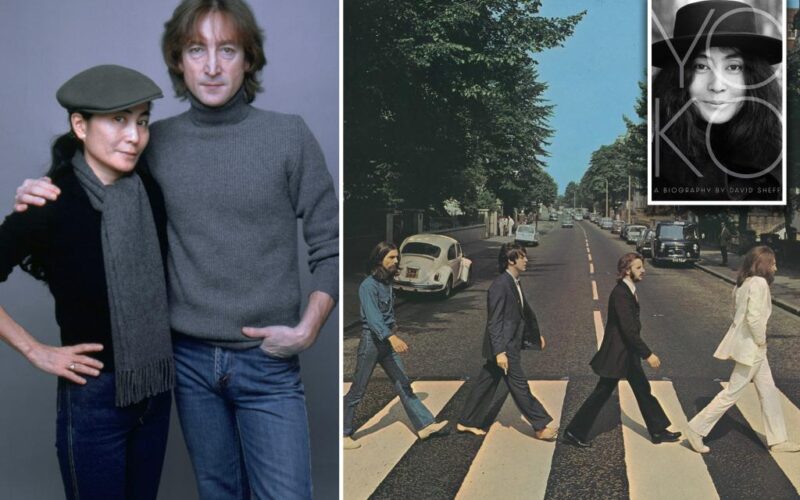

“There’s a version of the Beatles story in which there’d be no ‘Let It Be’ or ‘Abbey Road’ without Yoko. During the writing and recording of those albums, John had a foot out the door. If he hadn’t had Yoko, the other foot might have followed sooner than it did,” David Sheff writes in his expansive new book, “Yoko: A Biography,” (Simon & Schuster, out now).

“She accompanied John — literally holding his hand sometimes — to the sessions that resulted in the final Beatles albums,” continues Sheff, who interviewed the couple extensively in the month before Lennon’s death in December 1980.

Klaus Voormann, Lennon’s friend and the couple’s bandmate, notes that before he met Ono, Lennon had become so unhappy with his life that it would sometimes leave him in tears.

“Before he was with Yoko, John was in really bad shape,” Voormann says in the book. “When Yoko came, that changed one hundred percent. She gave him what he needed.”

Ono was born to one of Japan’s wealthiest and most influential families on February 18, 1933.

Her Tokyo childhood contained a multitude of servants and all the trappings of wealth, but it was also one of “emotional poverty,” according to the book.

Ono’s parents were not only emotionally distant, they shielded her from other children believing she was “too good for them,” and that they would “take advantage of her.”

“Yoko survived her childhood by escaping into her imagination,” writes Sheff. “She instinctively turned inward, spending hours sketching in a notebook and making up stories.”

In March of 1945, she was just 12-years-old when the United States firebombed the Japanese capital in the final stages of World War II. Her family was safely ensconced in a bomb shelter in their garden, but Ono, ill with fever, was too sick to be moved.

So she watched helplessly from her window, hearing the whistle of explosions and feeling the earth shake, as her city faced a relentless bombing campaign that left over 100,000 people dead.

In the aftermath, Ono went from a life of elite schools and privilege to scrounging for food and caring for her younger siblings in bombed-out, roofless homes. She attempted suicide numerous times as a teen, and several times again in the years just before she met Lennon.

Her lonely early life set the stage for her avant-garde art, which was sometimes dark, sometimes wildly optimistic.

She moved to the U.S. and settled in Greenwich Village in the 1950s — a peak era of creativity for the neighborhood. Ono began recording music and displaying and performing her art.

Her most famous exhibit was “Cut Piece,” which found Ono sitting cross-legged on stage as she invited the audience to come up and cut off pieces of her clothing with scissors.

Ono performed the piece — which would eventually be declared one of the most influential works of protest art of the century — several times over the years, enduring men who mimed stabbing her and others who cut off all her clothes in a frenzied mob.

Lennon met Ono in 1966 at an exhibit of hers called “Instruction Paintings” at Indica Gallery in London. At that point, she was married to film producer Anthony Cox and the two had a three-year-old daughter named Kyoko. Ono had previously been married to composer and pianist Toshi Ichiyanagi.

After the gallery’s owner introduced her to Lennon, she handed him a card with the word “Breath” on it.

The Beatle panted at her in response, and Ono replied, “That’s it. You’ve got it.”

While Lennon was the famous one, meeting Ono opened up his world.

“John was enchanted by the lightness and humor in Yoko’s work and moved by the pathos,” writes Sheff.

Ono, meanwhile, didn’t realize how big a deal her new paramour was.

“Rock and roll had passed me by,” Ono said. “I had [only] heard about the Beatles, and I knew the name Ringo, [which] hit me because ‘ringo’ is ‘apple’ in Japanese.”

Ono and Lennon maintained a platonic friendship for a year-and-a-half. On the Beatles famous trip to India, Lennon spent much of his time sending her postcards despite the presence of his first wife, Cynthia, with whom he had a young son, Julian.

Lennon later told Sheff that at the time, he was “trying to reach God and feeling suicidal,” and that the flurry of letters and postcards between him and Ono saved him.

“A typical postcard from Yoko was like an instruction from one of her events: ‘I’m a cloud. Watch for me in the sky,’” writes Sheff. “John said, ‘And I’d be looking up trying to see her, and then rushing down to the post office the next morning to get another message. It was driving me mad.’ He couldn’t stop thinking about her.”

The pair divorced their respective spouses, and married in March 1969. (Ono would barely get to see Kyoko over the years, amidst a messy custody battle and Cox raising their daughter in a series of cults. Ono and Lennon frequently tried to find her. Ono eventually reunited with Kyoko shortly after the girl

turned 30. The two have maintained a close relationship since.)

Sheff notes that Lennon officially broke up the Beatles on September 20, 1969. At a meeting at the Apple offices in London, he informed the other band members and their manager that he was “all in on his partnership with Yoko.”

The conversation turned to a discussion of a potential new record deal, and Lennon told them, “You don’t seem to understand, do you? The group is over. I’m leaving.”

“It was natural. John moved on,” Voorman says in the book.

Sheff writes that Lennon’s 1971 hit “Imagine,” his most famous and beloved post-Beatles song, was not only co-written with Ono — who did not receive credit — but was “a synthesis of Yoko’s philosophy and her conceptual art.”

In 1964, she’d released a book of drawings and instructional poems called “Grapefruit.” It had lines such as “Imagine one thousand suns in the sky at the same time,” and, “Imagine your head filled with pencil leads.” It would prove greatly influential to Lennon.

“Though John wrote the melody [for “Imagine”], the idea, title, and lyrics were inspired by Yoko’s concept of wish fulfillment,” Sheff writes. “It was specifically inspired, John said, by ‘Grapefruit.’”

In 1980, Lennon told Sheff that Ono had essentially been a cowriter on the song’s lyrics.

“I wasn’t man enough to let her have credit for it,” the music legend admitted to the writer the month before his assassination. “I was still selfish enough and unaware enough to sort of take her contribution without acknowledging it. The song ‘Imagine’ could never have been written without her.’”